Jack the Ripper once claimed that when historians looked back they would say that he gave birth to the 20th Century. And, in reality, his words have proven to be painfully true, for the psychotic and the serial killer function as symptoms of modernity to a certain degree and even more so for postmodernity. They are symptoms that our society has itself become pathological because of the power of the media image—the society of the spectacle as Guy De Bord would term it—the joint control of governments and multinational corporations, the increased alienation of labor, etc. In many ways, the conspiracy theories and delusions of psychotics have been implanted by

Jack the Ripper once claimed that when historians looked back they would say that he gave birth to the 20th Century. And, in reality, his words have proven to be painfully true, for the psychotic and the serial killer function as symptoms of modernity to a certain degree and even more so for postmodernity. They are symptoms that our society has itself become pathological because of the power of the media image—the society of the spectacle as Guy De Bord would term it—the joint control of governments and multinational corporations, the increased alienation of labor, etc. In many ways, the conspiracy theories and delusions of psychotics have been implanted by the media and global grid of control that doesn’t just exist in their minds any longer but has become the structure of our quotidian existence. In such a world in which the simulacrum overtakes reality, it is no wonder that the psychotic and the serial killer have become such heavily symbolic figures in fiction, film, and other media. As Lacan explains, the psychotic forecloses the signifier and engages in a subsequent resignification of the world—the psychotic attempts to create a hermetically sealed view of reality by resignifying everything, that is by developing his/her own semiology of existence. Hence, the psychotic becomes such a powerful figure because s/he represents an attempt to apply a stable meaning to the fragmented nature of postmodern existence—the serial killer becomes emblematic of our desire to reorder existence and become the solipsistic center of reality that doles out meaning in manner akin to God.

the media and global grid of control that doesn’t just exist in their minds any longer but has become the structure of our quotidian existence. In such a world in which the simulacrum overtakes reality, it is no wonder that the psychotic and the serial killer have become such heavily symbolic figures in fiction, film, and other media. As Lacan explains, the psychotic forecloses the signifier and engages in a subsequent resignification of the world—the psychotic attempts to create a hermetically sealed view of reality by resignifying everything, that is by developing his/her own semiology of existence. Hence, the psychotic becomes such a powerful figure because s/he represents an attempt to apply a stable meaning to the fragmented nature of postmodern existence—the serial killer becomes emblematic of our desire to reorder existence and become the solipsistic center of reality that doles out meaning in manner akin to God.

They Might Be Giants’ chipper tale of an incarcerated serial killer who compares himself to Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave.”

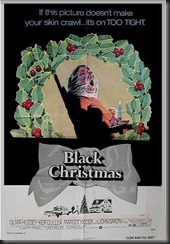

The golden age of the slasher film kicks off in 1978 with the release of John Carpenter’s Halloween, but two important pre-cursors deserve special mention: Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Bob Clark’s Black Christmas. Both released in 1974, these two films established many of the tropes that later slasher films would employ. Four years before John Carpenter's more famous Halloween, Bob Clark’s Canadian production Black Christmas appeared to little fanfare at the time. However, Black Christmas is a brutal, stylish, tense, and even hilarious film that laid down the basic structure of the slasher film without some of the clichés that would later come to define the genre. All of the basic elements of

The golden age of the slasher film kicks off in 1978 with the release of John Carpenter’s Halloween, but two important pre-cursors deserve special mention: Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Bob Clark’s Black Christmas. Both released in 1974, these two films established many of the tropes that later slasher films would employ. Four years before John Carpenter's more famous Halloween, Bob Clark’s Canadian production Black Christmas appeared to little fanfare at the time. However, Black Christmas is a brutal, stylish, tense, and even hilarious film that laid down the basic structure of the slasher film without some of the clichés that would later come to define the genre. All of the basic elements of the slasher genre are here: a group of attractive young college women, a holiday setting, creepy phone calls, point of view shots from the killer's perspective, an ever-growing body count, etc., etc. But Black Christmas is actually more twisted, better written, and more stylishly directed than the majority of the slasher films to follow. I place it

the slasher genre are here: a group of attractive young college women, a holiday setting, creepy phone calls, point of view shots from the killer's perspective, an ever-growing body count, etc., etc. But Black Christmas is actually more twisted, better written, and more stylishly directed than the majority of the slasher films to follow. I place it  above even Halloween in my book, but that's perhaps straying into contentious territory. Featuring the beautiful and talented Olivia Hussey (Juliet from Zeffirelli's 1968 version of Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet) and Margot Kidder (Lois Lane from Richard Donner’s Superman [1978]) as well as John Saxon (Enter the Dragon [1973], A Nightmare on Elm Street [1984]), Black Christmas features performers who can actually act and a script that is genuinely funny as well as tense and visceral. The film's depiction of serious social issues of

above even Halloween in my book, but that's perhaps straying into contentious territory. Featuring the beautiful and talented Olivia Hussey (Juliet from Zeffirelli's 1968 version of Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet) and Margot Kidder (Lois Lane from Richard Donner’s Superman [1978]) as well as John Saxon (Enter the Dragon [1973], A Nightmare on Elm Street [1984]), Black Christmas features performers who can actually act and a script that is genuinely funny as well as tense and visceral. The film's depiction of serious social issues of the time like abortion and its narrative ambiguity further mark it as a more serious and artful slasher films than those to come. Black Christmas’s ambiguity also marks it as an especially unique slasher text. The recent remake of the film eliminated this ambiguity by depicting the killer’s past and hence destroyed much of the creepy mystery that makes the original such a classic.

the time like abortion and its narrative ambiguity further mark it as a more serious and artful slasher films than those to come. Black Christmas’s ambiguity also marks it as an especially unique slasher text. The recent remake of the film eliminated this ambiguity by depicting the killer’s past and hence destroyed much of the creepy mystery that makes the original such a classic.

Original trailer for Black Christmas.

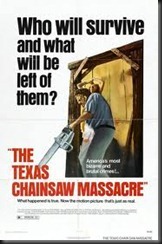

In the same year that Black Christmas hit theaters, another independent and more infamous horror film also landed in cinemas: Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. The film concerns a group of friends driving through rural Texas who pick up a mysterious hitchhiker and then end up falling victim to an inbred family of cannibals. Like Psycho (1960), Texas Chainsaw is loosely based on real-life serial killer Ed Gein—Gein also served as the inspiration for The Silence of the Lambs (1991). The film introduces the viewer to an entire family of cannibals, but it is Leatherface that became the iconic killer of the film. Mentally disabled and physically deformed, Leatherface enjoys butchering people like animals, running with chainsaws, and making new faces for himself by cutting them off his

In the same year that Black Christmas hit theaters, another independent and more infamous horror film also landed in cinemas: Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. The film concerns a group of friends driving through rural Texas who pick up a mysterious hitchhiker and then end up falling victim to an inbred family of cannibals. Like Psycho (1960), Texas Chainsaw is loosely based on real-life serial killer Ed Gein—Gein also served as the inspiration for The Silence of the Lambs (1991). The film introduces the viewer to an entire family of cannibals, but it is Leatherface that became the iconic killer of the film. Mentally disabled and physically deformed, Leatherface enjoys butchering people like animals, running with chainsaws, and making new faces for himself by cutting them off his victims. You can easily see the parallels between the taxidermy of Norman Bates in Psycho, the face-wearing of Hannibal Lector, and the full-body suit of Buffalo Bill (the latter two from The Silence of the Lambs). Grainy and cheap-looking, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre has a similar snuff-film aesthetic to other shocking independent films of the era like The Last House on the Left (1972). It feels visceral and real from its aesthetic to its macabre content, culminating in a cannibalistic dinner scene. Chainsaw Massacre has led to three sequels, a remake, and a prequel to the remake. Hooper directed the first sequel himself, but this sequel deviated from the original’s gritty realism and instead

victims. You can easily see the parallels between the taxidermy of Norman Bates in Psycho, the face-wearing of Hannibal Lector, and the full-body suit of Buffalo Bill (the latter two from The Silence of the Lambs). Grainy and cheap-looking, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre has a similar snuff-film aesthetic to other shocking independent films of the era like The Last House on the Left (1972). It feels visceral and real from its aesthetic to its macabre content, culminating in a cannibalistic dinner scene. Chainsaw Massacre has led to three sequels, a remake, and a prequel to the remake. Hooper directed the first sequel himself, but this sequel deviated from the original’s gritty realism and instead  became a silly and rather crappy horror comedy with Dennis Hopper as a double-chainsaw-wielding (he even has holsters for them) sheriff in search of the cannibal family who now compete in chili cook-offs using humans as their meat. The third sequel, which remained unreleased for many years, was actually the debut role of both Matthew McConaghey and Renee Zelwegger. The series has become classic epitome of torture cinema, and the entire so-called “torture porn” (Saw [2004], Hostel [2005], etc.) owes an infinite debt of gratitude to the films.

became a silly and rather crappy horror comedy with Dennis Hopper as a double-chainsaw-wielding (he even has holsters for them) sheriff in search of the cannibal family who now compete in chili cook-offs using humans as their meat. The third sequel, which remained unreleased for many years, was actually the debut role of both Matthew McConaghey and Renee Zelwegger. The series has become classic epitome of torture cinema, and the entire so-called “torture porn” (Saw [2004], Hostel [2005], etc.) owes an infinite debt of gratitude to the films.

The infamous dinner scene from near the end of Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

While the slasher genre had already appeared fully formed four years earlier in Bob Clark’s Black Christmas, it was John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) that inaugurated the so-called “Golden Age” of slasher films that lasted through the early 80s. John Carpenter’s Halloween burst on the scene in 1978 and ignited a phenomenon. Carptenter’s film concerns young Michael Myers who murders his sexually active sister one All Hallow’s Eve and then proceeds to be locked up in a mental asylum for his crime and mental instability. Many years later,

While the slasher genre had already appeared fully formed four years earlier in Bob Clark’s Black Christmas, it was John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) that inaugurated the so-called “Golden Age” of slasher films that lasted through the early 80s. John Carpenter’s Halloween burst on the scene in 1978 and ignited a phenomenon. Carptenter’s film concerns young Michael Myers who murders his sexually active sister one All Hallow’s Eve and then proceeds to be locked up in a mental asylum for his crime and mental instability. Many years later,  Myers breaks out of the institution, finds a William Shatner mask, and begins to stalk teenage Jamie Lee Curtis and her friends on Halloween. The results are absolutely classic: from the lengthy opening POV shot to the creepy lurking in the background moments, Halloween stole many moments from Black Christmas and made them canonical characteristics of the slasher film. As Myers kills off the expendable

Myers breaks out of the institution, finds a William Shatner mask, and begins to stalk teenage Jamie Lee Curtis and her friends on Halloween. The results are absolutely classic: from the lengthy opening POV shot to the creepy lurking in the background moments, Halloween stole many moments from Black Christmas and made them canonical characteristics of the slasher film. As Myers kills off the expendable teenagers, Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis) emerges as the paradigmatic final girl who has persevered through her intelligence and moral respectability. Halloween ignited the “Golden Age” of the slasher film and established Jamie Lee Curtis’s early career as a scream queen. Curtis appeared in the quick-to-follow sequel to

teenagers, Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis) emerges as the paradigmatic final girl who has persevered through her intelligence and moral respectability. Halloween ignited the “Golden Age” of the slasher film and established Jamie Lee Curtis’s early career as a scream queen. Curtis appeared in the quick-to-follow sequel to  Halloween, which picked up immediately after the original left off and followed Michael Myers as he terrorized Haddonfield’s hospital. Curtis then appeared in various rip-offs of Halloween like Prom Night (1980) and Terror Train (1980) as well as John Carpenter’s follow-up film, The Fog (1980). Halloween jumpstarted an entire industry of horror films that would come to dominate the horror market and the film market in general during the early 1980s.

Halloween, which picked up immediately after the original left off and followed Michael Myers as he terrorized Haddonfield’s hospital. Curtis then appeared in various rip-offs of Halloween like Prom Night (1980) and Terror Train (1980) as well as John Carpenter’s follow-up film, The Fog (1980). Halloween jumpstarted an entire industry of horror films that would come to dominate the horror market and the film market in general during the early 1980s.

The opening scene of Halloween, an almost five-minute long POV shot.

Black Christmas undoubtedly influenced Halloween, but the film also influenced another classic stalker film that appeared the year after Halloween: When a Stranger Calls (1979). Based on the urban legend of “The Babysitter and the Man Upstairs,” which also influenced Black Christmas, When a Stranger Calls concerns a babysitter who keeps receiving threatening calls until she discovers that the caller is actually already upstairs in the house. This basic story unfolds in the first twenty minutes of the film, and then the remainder of the movie concerns the futures of both the babysitter and the killer whose fates are destined to intertwine one more time. Although few would consider When a Stranger Calls a slasher film, it is a classic serial killer thriller that plays with elements of the slasher genre and profoundly influenced the slasher films that would follow. Its opening scene consistently ranks high on any list of the scariest scenes in cinematic history—check the scene out in the following three video clips.

Although few would consider When a Stranger Calls a slasher film, it is a classic serial killer thriller that plays with elements of the slasher genre and profoundly influenced the slasher films that would follow. Its opening scene consistently ranks high on any list of the scariest scenes in cinematic history—check the scene out in the following three video clips.

When a Stranger Calls opening scene, Part 1.

When a Stranger Calls opening scene, Part 2.

When a Stranger Calls opening scene, Part 3.

The second most influential slasher film appeared in 1980 and forever solidified the holiday-slasher structure. Sean Cunningham’s Friday the 13th (1980) arrived on the heels of Black Christmas and Halloween, introduced new levels of brutality and gore, and helped ensure the onslaught of slasher films that was to follow in the early 80s. Halloween introduced the first iconic slasher killer, Michael Myers, and Friday the 13th featured the second—Jason Voorhees. However, contrary to what many people think, Jason was not actually the killer in the original Friday the 13th—it

The second most influential slasher film appeared in 1980 and forever solidified the holiday-slasher structure. Sean Cunningham’s Friday the 13th (1980) arrived on the heels of Black Christmas and Halloween, introduced new levels of brutality and gore, and helped ensure the onslaught of slasher films that was to follow in the early 80s. Halloween introduced the first iconic slasher killer, Michael Myers, and Friday the 13th featured the second—Jason Voorhees. However, contrary to what many people think, Jason was not actually the killer in the original Friday the 13th—it was his mother, Mrs. Voorhees, who committed the killings in order to exact revenge upon the camp counselors who let her son Jason drown while they were having sex. In the sequel, which followed quickly a year later, Jason becomes the central killer as he seeks vengeance for the death of his mother; however, his iconic mask still did not make an appearance. It is not until Friday the 13th Part III (1982) that Jason finds his iconic hockey mask. The hockey mask stuck, and the series continued with nine sequels to the

was his mother, Mrs. Voorhees, who committed the killings in order to exact revenge upon the camp counselors who let her son Jason drown while they were having sex. In the sequel, which followed quickly a year later, Jason becomes the central killer as he seeks vengeance for the death of his mother; however, his iconic mask still did not make an appearance. It is not until Friday the 13th Part III (1982) that Jason finds his iconic hockey mask. The hockey mask stuck, and the series continued with nine sequels to the  original, a crossover with Freddy Krueger from A Nightmare on Elm St., and a recent remake of the original film. The success of Halloween and Friday the 13th ignited a firestorm of slasher films that centered around holidays or special events: Prom Night, Graduation Day (1981), Mother’s Day (1980), Silent Night Deadly Night (1984), April Fools Day (1986), Happy Birthday to Me (1981), New Year’s Evil (1980), My Blood Valentine (1981), The Slumber Party Massacre (1983), Welcome to Spring Break (1989), etc. These films were of varying quality, and non-holiday-themed slasher films also appeared during the period: Terror Train, The Prowler (1981), Pieces (1982),

original, a crossover with Freddy Krueger from A Nightmare on Elm St., and a recent remake of the original film. The success of Halloween and Friday the 13th ignited a firestorm of slasher films that centered around holidays or special events: Prom Night, Graduation Day (1981), Mother’s Day (1980), Silent Night Deadly Night (1984), April Fools Day (1986), Happy Birthday to Me (1981), New Year’s Evil (1980), My Blood Valentine (1981), The Slumber Party Massacre (1983), Welcome to Spring Break (1989), etc. These films were of varying quality, and non-holiday-themed slasher films also appeared during the period: Terror Train, The Prowler (1981), Pieces (1982), Curtains (1983), Madman (1982), Night Warning (1983), The House on Sorority Row (1983), etc. Pieces, in particular, is a nasty, overly brutal, hilarious, and bizarro slasher film that should be watched by anyone who enjoys the genre. Despite the formulaic nature of the films, the genre became so popular that slasher films supposedly accounted for 60% of ticket sales in 1983 before beginning to taper off and be considered cliché in the late 1980s.

Curtains (1983), Madman (1982), Night Warning (1983), The House on Sorority Row (1983), etc. Pieces, in particular, is a nasty, overly brutal, hilarious, and bizarro slasher film that should be watched by anyone who enjoys the genre. Despite the formulaic nature of the films, the genre became so popular that slasher films supposedly accounted for 60% of ticket sales in 1983 before beginning to taper off and be considered cliché in the late 1980s.

Original trailer for the first Friday the 13th—watch for an extremely young Kevin Bacon.

The scene from Friday the 13th Part III in which Jason first appears in his iconic hockey mask. The film was released in 3D.

Trailer for Pieces, one of the more extreme slasher films of the era.

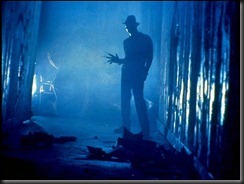

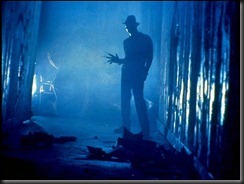

The great triumvirate of slasher bogeymen was rounded out in 1984 with the release of A Nightmare on Elm Street and the introduction of of Freddy Krueger. A Nightmare on Elm Street concerns a group of high schoolers who are tormented by the same bogeyman in their dreams. As their dreams lead to their deaths in real life, the teenagers discover the dark past of Elm Street: a child murderer named Fred Krueger was arrested and let off on a technicality, so the Elm Street parents gathered and burnt him to death in the boiler room where he used to take his children. In the film’s present, Fred Krueger (or Freddy) returns to kill the children of his murderers while they sleep. Played by Robert Englund, Freddy became the paradigmatic bogeyman of the 1980s. Now, one not only had to worry about being killed by maniacs in everyday reality, but this fear crept into the sanctity of one’s own mind—the sanctuary of dreams was violated by the phallic finger-knives of

kill the children of his murderers while they sleep. Played by Robert Englund, Freddy became the paradigmatic bogeyman of the 1980s. Now, one not only had to worry about being killed by maniacs in everyday reality, but this fear crept into the sanctity of one’s own mind—the sanctuary of dreams was violated by the phallic finger-knives of  Freddy. While Elm Street may seem dated and silly now, it remains a powerful exploration of the superstitions and fears we implicitly harbor about dreams. Are they the window into the unconscious like Freud and Lacan argue? If so, then how do we read their signifiers? Are they comprised of archetypes from the collective unconscious—an argument that could easily be applied to Krueger—as Jung would contend? Do they contain portents of the future or visions from God as so many different religious and superstitious traditions believe? Nothing can grip one with horror or

Freddy. While Elm Street may seem dated and silly now, it remains a powerful exploration of the superstitions and fears we implicitly harbor about dreams. Are they the window into the unconscious like Freud and Lacan argue? If so, then how do we read their signifiers? Are they comprised of archetypes from the collective unconscious—an argument that could easily be applied to Krueger—as Jung would contend? Do they contain portents of the future or visions from God as so many different religious and superstitious traditions believe? Nothing can grip one with horror or other powerful emotions like a dream, yet they vanish along with the twilit world in which they dance for only a few brief moments across the synapses of our brain. As Friedrich Nietzsche states of dreams, “Who knows the terror of he who falls asleep? The ground gives way beneath him. And the dream begins…..” Interestingly,

other powerful emotions like a dream, yet they vanish along with the twilit world in which they dance for only a few brief moments across the synapses of our brain. As Friedrich Nietzsche states of dreams, “Who knows the terror of he who falls asleep? The ground gives way beneath him. And the dream begins…..” Interestingly,  the 3D Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare (1991) begins with just this quote, which it quickly follows with a quote from Freddy himself: “Welcome to primetime bitch.” The first film was quickly followed by a succession of sequels that get progressively silly as Freddy devolves from a legitimate bogeyman to a macabre clown who kills in elaborate, fantastic scenarios while quipping one-liners that would make even the most “punny” of individuals cringe at their awfulness. Followed by six sequels, a crossover with Jason Voorhees in Freddy vs. Jason (2003), and a recent remake have kept the series alive and well for almost thirty years. Wes

the 3D Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare (1991) begins with just this quote, which it quickly follows with a quote from Freddy himself: “Welcome to primetime bitch.” The first film was quickly followed by a succession of sequels that get progressively silly as Freddy devolves from a legitimate bogeyman to a macabre clown who kills in elaborate, fantastic scenarios while quipping one-liners that would make even the most “punny” of individuals cringe at their awfulness. Followed by six sequels, a crossover with Jason Voorhees in Freddy vs. Jason (2003), and a recent remake have kept the series alive and well for almost thirty years. Wes Craven directed the first film and then eventually returned to the series for the meta-horror film Wes Craven’s A New Nightmare (1994). New Nightmare takes a metafictional approach to the series by focusing on the real lives of director Wes Craven, actor Robert Englund (Freddy), and actress Heather Langenkamp (Nancy) as Freddy begins to seep out of the films they made and into their reality. In many ways, New Nightmare seems like Craven was practicing for his later meta-horror hit, Scream (1996), a satirical take on the slasher genre

Craven directed the first film and then eventually returned to the series for the meta-horror film Wes Craven’s A New Nightmare (1994). New Nightmare takes a metafictional approach to the series by focusing on the real lives of director Wes Craven, actor Robert Englund (Freddy), and actress Heather Langenkamp (Nancy) as Freddy begins to seep out of the films they made and into their reality. In many ways, New Nightmare seems like Craven was practicing for his later meta-horror hit, Scream (1996), a satirical take on the slasher genre

Original trailer for A Nightmare on Elm Street.

An entertaining compilation of Freddy Krueger kill scenes from across the Nightmare series.

While the slasher film became all the rage in the early 80s, a more brutal and transgressive form of the genre was also appearing in films like William Lustig’s Maniac (1980) and Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986). Despite being over thirty years old, Maniac remains one of the most thoroughly brutal and disturbing slasher films ever. Instead of being told from the point of view of the victims, Maniac focalizes itself around Frank, the psycho-killer indicated in the film's not-so-subtle title. Despite Joe Spinell's inability to act, Maniac still manages to take the viewer on a descent into a world of pure insanity and brutal violence as Frank kills one person after another with gore effects courtesy of the legendary Tom Savini and then returns home to arrange and have bizarre conversations with mannequins. Joe Spinell looks like an extra ugly and creepy Ron Jeremy, and his disgusting qualities only serve to heighten the creepy and perverse qualities of the film despite his inability to read a single line in a compelling manner. An entirely brutal and completely insane film, Maniac lives up to

arrange and have bizarre conversations with mannequins. Joe Spinell looks like an extra ugly and creepy Ron Jeremy, and his disgusting qualities only serve to heighten the creepy and perverse qualities of the film despite his inability to read a single line in a compelling manner. An entirely brutal and completely insane film, Maniac lives up to  its title. Maniac has no deeper meanings or social commentaries--it is pure exploitation, but it is an exploitative descent into madness like few others. Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer is a no less disturbing but perhaps more socially conscious depiction of psychosis and pattern murders. Whereas Maniac revels in its brutal special effects, loud and graphic murder scenes, and depictions of absolute insanity, Henry chooses to depict the calm, quiet exterior that masks the underlying madness. Henry seems like a normal, working class guy who goes from one low-paying job to another and lives with a friend in a crappy place. Soon, his friend’s sister

its title. Maniac has no deeper meanings or social commentaries--it is pure exploitation, but it is an exploitative descent into madness like few others. Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer is a no less disturbing but perhaps more socially conscious depiction of psychosis and pattern murders. Whereas Maniac revels in its brutal special effects, loud and graphic murder scenes, and depictions of absolute insanity, Henry chooses to depict the calm, quiet exterior that masks the underlying madness. Henry seems like a normal, working class guy who goes from one low-paying job to another and lives with a friend in a crappy place. Soon, his friend’s sister begins living with them after escaping from a violent relationship. Henry and she begin to develop feelings for one another, but their relationship is endangered by her brother’s own sexual advances and Henry’s sociopathic, psychotic behavior that regularly manifests itself in actions such as theft, rape, and murder. Henry feels like a

begins living with them after escaping from a violent relationship. Henry and she begin to develop feelings for one another, but their relationship is endangered by her brother’s own sexual advances and Henry’s sociopathic, psychotic behavior that regularly manifests itself in actions such as theft, rape, and murder. Henry feels like a  genuine portrait of a serial killer from its cheap, independent aesthetic to its seemingly normal protagonist who murders in his free time. Plus, Henry and his friend steal a video camera and use it to document certain atrocities—such scenes give the film a found footage vibe that adds to its creepiness and realism. A powerful, unforgettable, and brutal film that will leave you feeling dirty for having watched it, Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer remains a masterpiece of the genre that continues to disgust and haunt audiences almost thirty years later.

genuine portrait of a serial killer from its cheap, independent aesthetic to its seemingly normal protagonist who murders in his free time. Plus, Henry and his friend steal a video camera and use it to document certain atrocities—such scenes give the film a found footage vibe that adds to its creepiness and realism. A powerful, unforgettable, and brutal film that will leave you feeling dirty for having watched it, Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer remains a masterpiece of the genre that continues to disgust and haunt audiences almost thirty years later.

The trailer for William Lustig’s Maniac. Watch for the cameo of special effects supervisor Tom Savini as the victim in the shotgun scene that opens this trailer.

A scene from Henry: Portrait of a serial killer in which Henry and his friend try to buy a black-market television. Brutality ensues…..

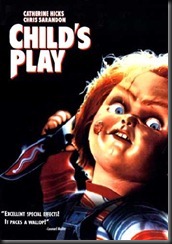

If one film killed off the golden age slasher film, it is probably Child’s Play (1988). Most critics cite the golden age as ending years earlier, but Child’s Play drives the final nail in the coffin because it becomes impossible to take the genre seriously any longer after seeing the somewhat realistic figure of the slasher reduced to an evil killer doll. Child’s Play follows a criminal who uses voodoo to transfer his spirit into a popular doll that was undoubtedly influenced by the popularity of Cabbage Patch kids during the 1980s. The original Child’s Play was a super -creepy, supernatural tale of terror in the vein of Richard Matheson’s classic horror short story “Prey” (1969) that introduced a potential fourth major slasher icon onto the market. But the sequels quickly devolved into self-conscious silliness. Four sequels turned Chucky into a buffoon even more laughable than the later Freddy. Bride of Chucky (1998) and Seed of Chucky (2004) actually became macabre comedy films more than horror as Chucky creates an evil female doll companion and eventually seeks to have a child with her.

-creepy, supernatural tale of terror in the vein of Richard Matheson’s classic horror short story “Prey” (1969) that introduced a potential fourth major slasher icon onto the market. But the sequels quickly devolved into self-conscious silliness. Four sequels turned Chucky into a buffoon even more laughable than the later Freddy. Bride of Chucky (1998) and Seed of Chucky (2004) actually became macabre comedy films more than horror as Chucky creates an evil female doll companion and eventually seeks to have a child with her.

The Geto Boys’ gangsta rap ode to Child’s Play. The band always enjoyed songs about lunatics and psycho killers.

Elliott Smith’s tender ballad that uses the Son of Sam as a metaphor.

Tune in next time for the 90s return to serial killer realism and the rise of torture porn….