Japan continued to produce more traditional horror cinema in the 1980s, but the decade also saw the release of a rather nasty strand of Japanese horror epitomized by films like Entrails of a Virgin (1986), Evil Dead Trap (1988), and the Guinea Pig series (1985-88). Entrails of the Virgin follows in the tradition of Horrors of Malformed Men, which I discussed in my last posting, because it blends sexual torture, gore, and fantastic elements together into a twisted work of exploitation cinema that will unnerve even the most hardened of horror/exploitation cinema fans. The film follows a group of

Japan continued to produce more traditional horror cinema in the 1980s, but the decade also saw the release of a rather nasty strand of Japanese horror epitomized by films like Entrails of a Virgin (1986), Evil Dead Trap (1988), and the Guinea Pig series (1985-88). Entrails of the Virgin follows in the tradition of Horrors of Malformed Men, which I discussed in my last posting, because it blends sexual torture, gore, and fantastic elements together into a twisted work of exploitation cinema that will unnerve even the most hardened of horror/exploitation cinema fans. The film follows a group of  photographers and models as they are killed one by one by a demon with a gigantic penis. The sex scenes are often fogged out to meet Japanese censorship standards. Almost openly misogynistic, Entrails of a Virgin is a truly disgusting film that was followed by an equally disgusting sequel: Entrails of Beautiful Woman (1988). While not as over-the-top and sexist as the Entrail films, Evil Dead Trap still signals a new era of brutality in Japanese horror cinema. The film concerns a female TV reporter who receives a snuff film that was shot at a local factory. She takes a crew to investigate the factory and discovers that the killer is actually a deformed fetus who is conjoined to his adult-size twin brother. Slowly, her crew fall victim to the killer in a series of bizarre and grisly murders. Neither the Entrails films or Evil Dead Trap are great films, but their gritty aesthetic, sexual violence, and high gore levels undoubtedly influenced Japanese horror and Asian horror more generally. The effects of such films can especially be seen in the brutal cinema of Takashi Miike, Park Chan Wook, and others that will be discussed below.

photographers and models as they are killed one by one by a demon with a gigantic penis. The sex scenes are often fogged out to meet Japanese censorship standards. Almost openly misogynistic, Entrails of a Virgin is a truly disgusting film that was followed by an equally disgusting sequel: Entrails of Beautiful Woman (1988). While not as over-the-top and sexist as the Entrail films, Evil Dead Trap still signals a new era of brutality in Japanese horror cinema. The film concerns a female TV reporter who receives a snuff film that was shot at a local factory. She takes a crew to investigate the factory and discovers that the killer is actually a deformed fetus who is conjoined to his adult-size twin brother. Slowly, her crew fall victim to the killer in a series of bizarre and grisly murders. Neither the Entrails films or Evil Dead Trap are great films, but their gritty aesthetic, sexual violence, and high gore levels undoubtedly influenced Japanese horror and Asian horror more generally. The effects of such films can especially be seen in the brutal cinema of Takashi Miike, Park Chan Wook, and others that will be discussed below.

Also released in the late 80s, the Guinea Pig series remains one of the most infamous groups of film ever to be released. Certain entries in the series still feature prominently on any list of the most twisted, disturbing, and hard to watch films ever. With some variation, the film series basically consists of extremely graphic depictions of women being slowly tortured and murdered. In fact, the most infamous entry in the series Guinea Pig 4: Flower of Flesh and Blood (1985) caused Charlie Sheen to contact the FBI after watching the film because he believed it was an actual snuff

Also released in the late 80s, the Guinea Pig series remains one of the most infamous groups of film ever to be released. Certain entries in the series still feature prominently on any list of the most twisted, disturbing, and hard to watch films ever. With some variation, the film series basically consists of extremely graphic depictions of women being slowly tortured and murdered. In fact, the most infamous entry in the series Guinea Pig 4: Flower of Flesh and Blood (1985) caused Charlie Sheen to contact the FBI after watching the film because he believed it was an actual snuff  film, a snuff film being a type of film in which actual deaths are captured on camera—the FBI maintains that no actual snuff film has ever been discovered and that they are merely urban legends. Like Entrails of a Virgin, the Guinea Pig films are basically unredeemable except in their brilliant usage of special effects. They are nauseating, boring, plotless, misogynistic, exploitation films that contain no purpose other than to shock the audience.

film, a snuff film being a type of film in which actual deaths are captured on camera—the FBI maintains that no actual snuff film has ever been discovered and that they are merely urban legends. Like Entrails of a Virgin, the Guinea Pig films are basically unredeemable except in their brilliant usage of special effects. They are nauseating, boring, plotless, misogynistic, exploitation films that contain no purpose other than to shock the audience.

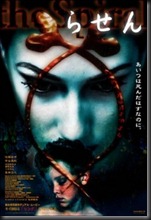

Asian horror cinema made a splash in the United States with the release of Hideo Nakata’s Ringu (1998) and its American remake by Gore Verbinsky—The Ring (2002). Ringu concerns a videotape that kills its viewers seven days after they watch it. Ringu inaugurated a trend of Asian horror films that focused upon technology and its potential to be haunted. In essence, Ringu is a film about the power that technology wields over ours lives. While its usage of a videocassette may seem dated now in our Blu-Ray world, the film still resonates as a compelling meditation upon how technology captures us and suggests that it may affect us down to the core of our souls. Based on Koji Suzuki’s Ringu novels (1991-9), Nakata’s Ringu was followed by two different sequels (Rasen

Asian horror films that focused upon technology and its potential to be haunted. In essence, Ringu is a film about the power that technology wields over ours lives. While its usage of a videocassette may seem dated now in our Blu-Ray world, the film still resonates as a compelling meditation upon how technology captures us and suggests that it may affect us down to the core of our souls. Based on Koji Suzuki’s Ringu novels (1991-9), Nakata’s Ringu was followed by two different sequels (Rasen  [1998; another word that means “spiral”] and Ringu 2 [1999]) as well as a prequel (Ringu 0 [2000]). Ringu, and films like it, brought the kaidan genre into the postmodern era and developed a horrifying, creepy aesthetic that influenced cinema around the globe. Hideo Nakata, the director of Ringu, went on to direct another J-Horror classic entitled Dark Water (2002), which was also remade as an American film, and his own film called Kaidan (2007) that also drew upon a tale from Lafcadio Hearn’s collection. While the depiction of yurei (ghosts)

[1998; another word that means “spiral”] and Ringu 2 [1999]) as well as a prequel (Ringu 0 [2000]). Ringu, and films like it, brought the kaidan genre into the postmodern era and developed a horrifying, creepy aesthetic that influenced cinema around the globe. Hideo Nakata, the director of Ringu, went on to direct another J-Horror classic entitled Dark Water (2002), which was also remade as an American film, and his own film called Kaidan (2007) that also drew upon a tale from Lafcadio Hearn’s collection. While the depiction of yurei (ghosts)  with long, disheveled black hair dates back for centuries in Japanese literature, theatre, and painting, it was Ringu that introduced the world to the creepy girl with long black hair that often seems to have a life of its own. Ringu also inaugurated a series of films about haunted technology: Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse (2001), Phone, and Takashi Miike’s One Missed Call (2003) represent the most famous of these technophobic horror films.

with long, disheveled black hair dates back for centuries in Japanese literature, theatre, and painting, it was Ringu that introduced the world to the creepy girl with long black hair that often seems to have a life of its own. Ringu also inaugurated a series of films about haunted technology: Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse (2001), Phone, and Takashi Miike’s One Missed Call (2003) represent the most famous of these technophobic horror films.

The cursed video from Gore Verbinski’s remake, which in many ways improves upon the version from Ringu.

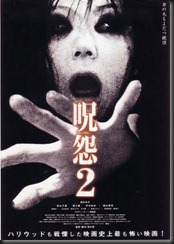

Aside from Ringu, Ju-On (or The Grudge) remains the second most famous J-horror film in the United States. Ju-On has actually be remade numerous times by director Takashi Shimizu. Ju-On translates roughly as “the curse” or “the grudge.” Shimizu released the original Ju-On (2000) and Ju-On 2 (2000) as direct-to-video, or V-Cinema films. The films became a hit through word of mouth, and Shimizu directed a bigger-budget, theatrical version of Ju-On (2003) and Ju-On 2 (2003). The films were such a success that Shimizu even signed on to direct the American remake, entitled The Grudge (2004), starring Sarah Michelle

Aside from Ringu, Ju-On (or The Grudge) remains the second most famous J-horror film in the United States. Ju-On has actually be remade numerous times by director Takashi Shimizu. Ju-On translates roughly as “the curse” or “the grudge.” Shimizu released the original Ju-On (2000) and Ju-On 2 (2000) as direct-to-video, or V-Cinema films. The films became a hit through word of mouth, and Shimizu directed a bigger-budget, theatrical version of Ju-On (2003) and Ju-On 2 (2003). The films were such a success that Shimizu even signed on to direct the American remake, entitled The Grudge (2004), starring Sarah Michelle Gellar and Bill Pullman (yes, from Lost Highway!). For me, the American remake loses some of the weirdness inherent in the original, theatrical Ju-On that concerns a house that is haunted by the horrific rage of the children who were murdered there. There is a certain bizarre, uncanny vibe along with the horrific elements that is simply not present in the American version. I’m gonna go ahead and blame it on Sarah Michelle Gellar—I’m pretty sure it has to be her fault. Shimizu then even went on to direct The Grudge 2 (2006) for American theaters as well, which means that he has literally directed three different versions of both films. Like Ringu, the Ju-On films feature traditional yurei figures that persist because of the crimes committed against them. But Ju-On deviates a little by having both male and female ghosts—yurei are generally female.

Gellar and Bill Pullman (yes, from Lost Highway!). For me, the American remake loses some of the weirdness inherent in the original, theatrical Ju-On that concerns a house that is haunted by the horrific rage of the children who were murdered there. There is a certain bizarre, uncanny vibe along with the horrific elements that is simply not present in the American version. I’m gonna go ahead and blame it on Sarah Michelle Gellar—I’m pretty sure it has to be her fault. Shimizu then even went on to direct The Grudge 2 (2006) for American theaters as well, which means that he has literally directed three different versions of both films. Like Ringu, the Ju-On films feature traditional yurei figures that persist because of the crimes committed against them. But Ju-On deviates a little by having both male and female ghosts—yurei are generally female.

The infamous staircase scene from Ju-on. Interestingly, the director’s cut version of The Exorcist features a similar scene of Regan (Linda Blair) descending a staircase.

Here is the comparable scene from the director’s cut version of The Exorcist, the nastiest little addition to that version of the film.

The 1990s also saw the rise of one Japanese cinema’s great contemporary auteurs: Takashi Miike. Since bursting onto the scene in late 90s, Miike has directed films at a frenetic pace matched only by other genre directors like Roger Corman (A Bucket of Blood [1959], Little Shop of Horrors [1960], The Pit and the Pendulum [1961], Masque of the Red Death [1964], etc.) and Spanish B-movie maestro Jess Franco, who supposedly has directed over 200 films, some of which include The Awful Dr. Orloff (1962), Vampyros Lesbos (1971), A Virgin Among the Living Dead (1973), and countless adaptations of works by the Marquis de Sade. Miike began his career in television and direct-to-video cinema (or V-Cinema), and he

The 1990s also saw the rise of one Japanese cinema’s great contemporary auteurs: Takashi Miike. Since bursting onto the scene in late 90s, Miike has directed films at a frenetic pace matched only by other genre directors like Roger Corman (A Bucket of Blood [1959], Little Shop of Horrors [1960], The Pit and the Pendulum [1961], Masque of the Red Death [1964], etc.) and Spanish B-movie maestro Jess Franco, who supposedly has directed over 200 films, some of which include The Awful Dr. Orloff (1962), Vampyros Lesbos (1971), A Virgin Among the Living Dead (1973), and countless adaptations of works by the Marquis de Sade. Miike began his career in television and direct-to-video cinema (or V-Cinema), and he still makes some films for the direct-to-video market because of the laxer censhorship rules on such releases in Japan. Miike made a name for himself with his early gangster films, but he became truly famous with the release of his romantic horror film Audition (1999), which still reigns high on lists of the most disturbing films ever. Audition set the stage for what was to come—stylish, brutal, and poignant, Audition demonstrated how Miike could take seemingly cliched genre plots and turn them into something provocative, dangerous, and original. Audition concerns a widowed man who holds an mock-audition to find his new wife. He finds his true love, but she turns out to be way more than he bargained for. We almost watched Audition in this class, but I decided that the final scene of was just too much to ask a class to sit through.

still makes some films for the direct-to-video market because of the laxer censhorship rules on such releases in Japan. Miike made a name for himself with his early gangster films, but he became truly famous with the release of his romantic horror film Audition (1999), which still reigns high on lists of the most disturbing films ever. Audition set the stage for what was to come—stylish, brutal, and poignant, Audition demonstrated how Miike could take seemingly cliched genre plots and turn them into something provocative, dangerous, and original. Audition concerns a widowed man who holds an mock-audition to find his new wife. He finds his true love, but she turns out to be way more than he bargained for. We almost watched Audition in this class, but I decided that the final scene of was just too much to ask a class to sit through.  However, if you are a fan of horror cinema, I strongly urge you to watch it—it is a powerfully emotional and visceral horror experience that you will not forget. Since Audition, Miike has gone on to direct films in all types of genres: horror, gangster/Yakuza films, action, thrillers, children’s films, philosophical art films, fantasies, science fiction, samurai films, westerns, and even a truly bizarre musical. Miike’s films always feature a distinctive aesthetic, but many of his films could be classified as transgressive cinema because of their horrific blend of eroticism, graphic violence, gore, torture, rape, and even more disturbing subject matter that I won’t mention here. He

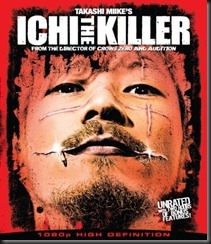

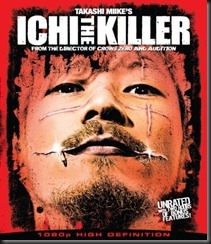

However, if you are a fan of horror cinema, I strongly urge you to watch it—it is a powerfully emotional and visceral horror experience that you will not forget. Since Audition, Miike has gone on to direct films in all types of genres: horror, gangster/Yakuza films, action, thrillers, children’s films, philosophical art films, fantasies, science fiction, samurai films, westerns, and even a truly bizarre musical. Miike’s films always feature a distinctive aesthetic, but many of his films could be classified as transgressive cinema because of their horrific blend of eroticism, graphic violence, gore, torture, rape, and even more disturbing subject matter that I won’t mention here. He  probably remains most infamous for his film Ichi the Killer (2001), a hyper-sadistic, bizarro Yakuza film. While Audition may rank high on lists of the most disturbing or scariest films ever, Ichi the Killer almost inevitably makes the top ten in lists of the sickest or most twisted films ever. Featuring an almost constant barrage

probably remains most infamous for his film Ichi the Killer (2001), a hyper-sadistic, bizarro Yakuza film. While Audition may rank high on lists of the most disturbing or scariest films ever, Ichi the Killer almost inevitably makes the top ten in lists of the sickest or most twisted films ever. Featuring an almost constant barrage  of mutilation, rape, torture, and murder, Ichi the Killer is perhaps one of the most nihilistic film experiences you can ever have and is not recommended for the faint of heart. That being said, it is also imbued with Miike’s bizarre sense of humor that—if anything—only makes the film more disturbing. But for me, Miike’s Visitor Q (2001) remains his most twisted and disturbing film. A tale of bullying and reality television, Visitor Q concerns a family completely neuroticized by various forms of bullying, and it features the other unmentionably horrific elements that I hinted at above. A disgusting, disturbing, and brutalizing black comedy, Visitor Q remains in the top of my personal list of the most disturbingly sick films ever.

of mutilation, rape, torture, and murder, Ichi the Killer is perhaps one of the most nihilistic film experiences you can ever have and is not recommended for the faint of heart. That being said, it is also imbued with Miike’s bizarre sense of humor that—if anything—only makes the film more disturbing. But for me, Miike’s Visitor Q (2001) remains his most twisted and disturbing film. A tale of bullying and reality television, Visitor Q concerns a family completely neuroticized by various forms of bullying, and it features the other unmentionably horrific elements that I hinted at above. A disgusting, disturbing, and brutalizing black comedy, Visitor Q remains in the top of my personal list of the most disturbingly sick films ever.

Trailer for Ichi the Killer. “There is no love in your violence.”

But my personal favorite Miike film remains Gozu (2003), a surrealistic Yakuza horror film with a David Lynch style aesthetic. Gozu, which literally means cow-headed, starts off as the story of two Yakuza men, one a lowly driver and the other a Yakuza captain. The captain has become paranoid and crazy, and so the Yakuza boss asks the driver to help dispose of the captain since he has become a liability. The captain apparently dies during a driving mishap and then his body inexplicably disappears. What follows is a nightmarish descent into madness and the supernatural:

But my personal favorite Miike film remains Gozu (2003), a surrealistic Yakuza horror film with a David Lynch style aesthetic. Gozu, which literally means cow-headed, starts off as the story of two Yakuza men, one a lowly driver and the other a Yakuza captain. The captain has become paranoid and crazy, and so the Yakuza boss asks the driver to help dispose of the captain since he has become a liability. The captain apparently dies during a driving mishap and then his body inexplicably disappears. What follows is a nightmarish descent into madness and the supernatural: an organization that collects human milk, potential demons, a Yakuza with a fetish I won’t even begin to mention, and a horrendous “birth” scene that has become iconic. Brutal and bizarre, Gozu plays like a super-perverted, sadistic version of David Lynch—it is Lost Highway retold by the Marquis de Sade. But Miike’s films have not all be of the transgressive, horror, or Yakuza varieties. Even

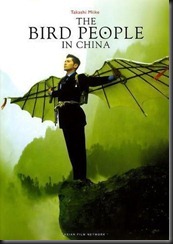

an organization that collects human milk, potential demons, a Yakuza with a fetish I won’t even begin to mention, and a horrendous “birth” scene that has become iconic. Brutal and bizarre, Gozu plays like a super-perverted, sadistic version of David Lynch—it is Lost Highway retold by the Marquis de Sade. But Miike’s films have not all be of the transgressive, horror, or Yakuza varieties. Even  early on his career, he helmed artful projects like The Bird People in China (1998), an existential fable about a Japanese businessman who travels to a remote village in China where, according to legend, the people can supposedly fly. A mournful, meditative, and beautiful film about the infinite possibilities that exist within the human, The Bird People in China hearkens back more to Japanese folktales or the tender cinema of Yasujiro Ozu than it does to Miike’s generally violent and sexual filmmography. To try and touch upon all of Miike’s body of work is

early on his career, he helmed artful projects like The Bird People in China (1998), an existential fable about a Japanese businessman who travels to a remote village in China where, according to legend, the people can supposedly fly. A mournful, meditative, and beautiful film about the infinite possibilities that exist within the human, The Bird People in China hearkens back more to Japanese folktales or the tender cinema of Yasujiro Ozu than it does to Miike’s generally violent and sexual filmmography. To try and touch upon all of Miike’s body of work is impossible in a short space, but he has also made countless Yakuza films (Dead or Alive [1999], etc.), science fiction (Full Metal Yakuza [1997]), samurai films (Izo [2004]), a children’s fantasy film (The Great Yokai War [2005]), and even a horror musical (The Happiness of the Katakuris [2001]).

impossible in a short space, but he has also made countless Yakuza films (Dead or Alive [1999], etc.), science fiction (Full Metal Yakuza [1997]), samurai films (Izo [2004]), a children’s fantasy film (The Great Yokai War [2005]), and even a horror musical (The Happiness of the Katakuris [2001]).

Among the recent generation of horror and transgressive filmmakers, Takashi Miike has become an iconic figure, as evidenced by his beginning to crossover into American cinema. In Eli Roth’s torture-porn classic Hostel (2005), Miike makes a small appearance as one of the rich guests who pay to torture and murder people. More recently, he helmed his first English-language film: Sukiyaki Western Django (2007), a postmodern pastiche that plays upon the cross-breeding between Samurai and Western films in the 1960s and 70s.

Among the recent generation of horror and transgressive filmmakers, Takashi Miike has become an iconic figure, as evidenced by his beginning to crossover into American cinema. In Eli Roth’s torture-porn classic Hostel (2005), Miike makes a small appearance as one of the rich guests who pay to torture and murder people. More recently, he helmed his first English-language film: Sukiyaki Western Django (2007), a postmodern pastiche that plays upon the cross-breeding between Samurai and Western films in the 1960s and 70s.  The title of the film itself announces this connection with its cross-cultural title: sukiyaki is a traditional Japanese dish, western of course refers to the popular American genre, and Django (1966) is the title of Sergio Corbucci’s classic spaghetti western. Hence, the film’s title already signifies that the film will play with the cross-pollination between American, Japanese, and Italian cinema. Most famously, Akira Kurosawa’s classic

The title of the film itself announces this connection with its cross-cultural title: sukiyaki is a traditional Japanese dish, western of course refers to the popular American genre, and Django (1966) is the title of Sergio Corbucci’s classic spaghetti western. Hence, the film’s title already signifies that the film will play with the cross-pollination between American, Japanese, and Italian cinema. Most famously, Akira Kurosawa’s classic  samurai film Yojimbo (1961) was remade as Sergio Leone’s classic western A Fistful of Dollars (1964)—Yojimbo itself was most likely based on Dashiell Hammett’s classic hard-boiled novel Red Harvest (1929). Like Red Harvest, Yojimbo, A Fistful of Dollars, and Sukiyaki Western Django concern the war between two rival gangs. Miike ups the ante even further by openly drawing comparisons between the conflict and

samurai film Yojimbo (1961) was remade as Sergio Leone’s classic western A Fistful of Dollars (1964)—Yojimbo itself was most likely based on Dashiell Hammett’s classic hard-boiled novel Red Harvest (1929). Like Red Harvest, Yojimbo, A Fistful of Dollars, and Sukiyaki Western Django concern the war between two rival gangs. Miike ups the ante even further by openly drawing comparisons between the conflict and  England’s War of the Roses—the film even includes quotes from Shakespeare’s dramatization of the events in Henry VI Part I, II, and III, his history tetralogy that of course culminates in the famous Richard III. Ultimately, Sukiyaki Western Django is almost incomprehensible plotwise, but it is a visually dazzling exploration of the influences that flow between western and eastern cinema. The appearance of Quentin Tarantino as a character in the film further solidifies Miike’s reputation as an international icon.

England’s War of the Roses—the film even includes quotes from Shakespeare’s dramatization of the events in Henry VI Part I, II, and III, his history tetralogy that of course culminates in the famous Richard III. Ultimately, Sukiyaki Western Django is almost incomprehensible plotwise, but it is a visually dazzling exploration of the influences that flow between western and eastern cinema. The appearance of Quentin Tarantino as a character in the film further solidifies Miike’s reputation as an international icon.

The trailer for Miike’s Sukiyaki Western Django, his homage to the connections between American westerns and Japanese samurai films.

Horror has also proliferated in Asian countries aside from Japan. While countries like Thailand and South Korea have been making horror films for decades, they have—like Japan—experienced a genuine renaissance of the form since the late 90s. For example, the Pang Brothers from Hong Kong have become a major force in Asian and American horror cinema—they have released films both in the Thai and American film marketplaces. They probably remain best known for their film The Eye (2002), which concerns a blind woman who receives a corneal transplant and then begins to see dead people—this film also received an American remake starring Jessica Alba, an actress who, like Sarah Michelle Gellar, almost

Horror has also proliferated in Asian countries aside from Japan. While countries like Thailand and South Korea have been making horror films for decades, they have—like Japan—experienced a genuine renaissance of the form since the late 90s. For example, the Pang Brothers from Hong Kong have become a major force in Asian and American horror cinema—they have released films both in the Thai and American film marketplaces. They probably remain best known for their film The Eye (2002), which concerns a blind woman who receives a corneal transplant and then begins to see dead people—this film also received an American remake starring Jessica Alba, an actress who, like Sarah Michelle Gellar, almost assures that a film will suck. Alba at least has a few exceptions I must admit: Sin City (2005), The Killer Inside Me (2010), and Machete (2010). But her performance is certainly not what makes these films good; in fact, she and Lindsay Lohan were clearly cast by Robert Rodriguez because they are awful—yet hot—actresses. The Pang brothers released two sequels to The Eye: The Eye 2 (2004) and The Eye 10 (2005). Both films were unrelated to the first film except in protagonists’ ability to see ghosts. The

assures that a film will suck. Alba at least has a few exceptions I must admit: Sin City (2005), The Killer Inside Me (2010), and Machete (2010). But her performance is certainly not what makes these films good; in fact, she and Lindsay Lohan were clearly cast by Robert Rodriguez because they are awful—yet hot—actresses. The Pang brothers released two sequels to The Eye: The Eye 2 (2004) and The Eye 10 (2005). Both films were unrelated to the first film except in protagonists’ ability to see ghosts. The  duo’s first film was Bangkok Dangerous (1999), which was remade in the U.S. as a terrible-looking Nicolas Cage film—they also helmed the remake. In 2006, they released what—to me at least—remains their masterpiece: the horror-fantasy film Re-Cycle. Re-Cycle concerns a young, female novelist who is having trouble working on her new book about the supernatural. Soon, she begins experiencing supernatural phenomena and is eventually transported to a fantastic, other world where the things we discard live on in exile. It is a stylish, creepy, and powerful film about our memories, the objects we leave behind, and the parts of ourselves

duo’s first film was Bangkok Dangerous (1999), which was remade in the U.S. as a terrible-looking Nicolas Cage film—they also helmed the remake. In 2006, they released what—to me at least—remains their masterpiece: the horror-fantasy film Re-Cycle. Re-Cycle concerns a young, female novelist who is having trouble working on her new book about the supernatural. Soon, she begins experiencing supernatural phenomena and is eventually transported to a fantastic, other world where the things we discard live on in exile. It is a stylish, creepy, and powerful film about our memories, the objects we leave behind, and the parts of ourselves we discard as we move into the future. A poignant horror film that explores deep philosophical themes, Re-Cycle remains the film that truly demonstrates the Pang Brother’s cinematic potential. Subsequently, the Pang brothers made their debut on the American film market with The Messengers (2007), a horror film starring a pre-Twilight Kristen Stewart, Dylan McDermott, and Penelope Ann Miller. The Messengers is a stylish—if not perfect—horror film about a family who gives up their city lives to become farmers only to discover that supernatural occurrences haunt the farm.

we discard as we move into the future. A poignant horror film that explores deep philosophical themes, Re-Cycle remains the film that truly demonstrates the Pang Brother’s cinematic potential. Subsequently, the Pang brothers made their debut on the American film market with The Messengers (2007), a horror film starring a pre-Twilight Kristen Stewart, Dylan McDermott, and Penelope Ann Miller. The Messengers is a stylish—if not perfect—horror film about a family who gives up their city lives to become farmers only to discover that supernatural occurrences haunt the farm.

Thai horror cinema has also released other minor, contemporary classics of Asian horror such as Art of the Devil (2004) and Shutter (also 2004). Tanit Jitnukul’s Art of the Devil concerns a young woman who learns she is pregnant only to have her boyfriend ditch her. Of course, she promptly begins to learn black magic in order to exact her revenge. The film developed enough of a cult following to spawn two sequels. Banjong Pisanthankun and Parkpoom Wongpoom’s Shutter, on the other hand,

Thai horror cinema has also released other minor, contemporary classics of Asian horror such as Art of the Devil (2004) and Shutter (also 2004). Tanit Jitnukul’s Art of the Devil concerns a young woman who learns she is pregnant only to have her boyfriend ditch her. Of course, she promptly begins to learn black magic in order to exact her revenge. The film developed enough of a cult following to spawn two sequels. Banjong Pisanthankun and Parkpoom Wongpoom’s Shutter, on the other hand,  represents yet another technophobic Asian horror film about a man who begins to notice ghostly images in his photographs after participating in a hit-and-run accident. Here’s a tip for you based on horror films—it’s always a bad idea to leave the scene of a car accident. Despite its somewhat clichéd premise, Shutter manages to be a decently creepy horror film, and it, of course, received its own American remake in 2008, featuring Joshua (Dawson’s Creek) Jackson.

represents yet another technophobic Asian horror film about a man who begins to notice ghostly images in his photographs after participating in a hit-and-run accident. Here’s a tip for you based on horror films—it’s always a bad idea to leave the scene of a car accident. Despite its somewhat clichéd premise, Shutter manages to be a decently creepy horror film, and it, of course, received its own American remake in 2008, featuring Joshua (Dawson’s Creek) Jackson.

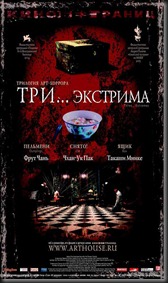

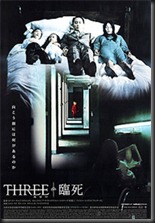

The renaissance in Asian horror cinema was celebrated by the two films Three (2002) and Three…Extremes (2004)—in the United States, Three was actually released as Three…Extremes 2. Both films had the same concept and structure—they are both omnibus films that feature three short films from three different directors who are from three different Asian nations. Three featured tales helmed by South Korean director Kim Ji-woon, Thai director Nonzee Nimibutr, and Hong Kong

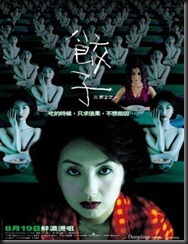

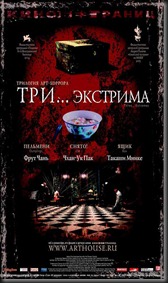

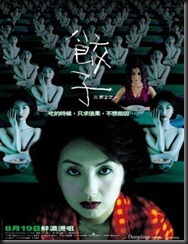

The renaissance in Asian horror cinema was celebrated by the two films Three (2002) and Three…Extremes (2004)—in the United States, Three was actually released as Three…Extremes 2. Both films had the same concept and structure—they are both omnibus films that feature three short films from three different directors who are from three different Asian nations. Three featured tales helmed by South Korean director Kim Ji-woon, Thai director Nonzee Nimibutr, and Hong Kong  director Peter Chan. The sequel remains more famous in the U.S. because of its more prestigious line-up of filmmakers: Fruit Chain (Hong Kong), Park Chan-wook (South Korea), and Takashi Miike (Japan). Each of these three directors in Three…Extremes contributes a powerful piece of cinema, but the anthology film remains most famous for Fruit Chan’s Dumplings, which has been released in an extended format as its own film. Dumplings concerns a middle-aged woman who is beginning to lose her

director Peter Chan. The sequel remains more famous in the U.S. because of its more prestigious line-up of filmmakers: Fruit Chain (Hong Kong), Park Chan-wook (South Korea), and Takashi Miike (Japan). Each of these three directors in Three…Extremes contributes a powerful piece of cinema, but the anthology film remains most famous for Fruit Chan’s Dumplings, which has been released in an extended format as its own film. Dumplings concerns a middle-aged woman who is beginning to lose her  youthfulness and seeks out the aid of a local chef who purportedly cooks special dumplings that can restore beauty. The only catch is that the dumplings contain aborted fetuses, a fact that the woman realizes upon her first visit; however, she proceeds to eat the dumplings anyway. What ensues is a horror tale about superficiality, the cult of beauty, and the dangers of vanity.

youthfulness and seeks out the aid of a local chef who purportedly cooks special dumplings that can restore beauty. The only catch is that the dumplings contain aborted fetuses, a fact that the woman realizes upon her first visit; however, she proceeds to eat the dumplings anyway. What ensues is a horror tale about superficiality, the cult of beauty, and the dangers of vanity.

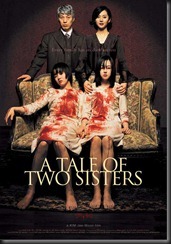

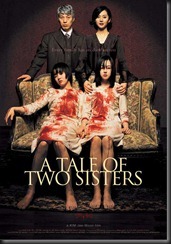

Finally, South Korean cinema has also developed its own distinct strain of horror, particularly with original, visionary directors like Kim Ji-woon and Park Chan-wook, who both made contributions to Three and Three…Extremes. Kim Ji-woon remains most famous for his creepy and stylish supernatural thriller A Tale of Two Sisters (2003)—its Korean title actually translates literally as “Rose Flower, Red Lotus.” Two Sisters was remade in the United States as The Uninvited (2009), starring the oddly cast comedic actress Elizabeth Banks (Scrubs, 30 Rock, Zach and Miri

Finally, South Korean cinema has also developed its own distinct strain of horror, particularly with original, visionary directors like Kim Ji-woon and Park Chan-wook, who both made contributions to Three and Three…Extremes. Kim Ji-woon remains most famous for his creepy and stylish supernatural thriller A Tale of Two Sisters (2003)—its Korean title actually translates literally as “Rose Flower, Red Lotus.” Two Sisters was remade in the United States as The Uninvited (2009), starring the oddly cast comedic actress Elizabeth Banks (Scrubs, 30 Rock, Zach and Miri  Make a Porno, etc.) in a villain role. Two Sisters features many of the hallmarks of Japanese and Asian horror, and it remains one of the masterpieces of the supernatural sub-genre of Asian horror. But Kim Ji-woon has since moved on to other genres. In 2008, he released a western entitled The Good, The Bad, The Weird, which went on to gain critical acclaims among cult cinema enthusiasts—the film was, of course, inspired by Sergio Leone’s spaghetti western masterpiece The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (2008). Recently, he released I Saw the Devil (2010), a thriller about a brutal serial killer and the man who vows to exact revenge on him.

Make a Porno, etc.) in a villain role. Two Sisters features many of the hallmarks of Japanese and Asian horror, and it remains one of the masterpieces of the supernatural sub-genre of Asian horror. But Kim Ji-woon has since moved on to other genres. In 2008, he released a western entitled The Good, The Bad, The Weird, which went on to gain critical acclaims among cult cinema enthusiasts—the film was, of course, inspired by Sergio Leone’s spaghetti western masterpiece The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (2008). Recently, he released I Saw the Devil (2010), a thriller about a brutal serial killer and the man who vows to exact revenge on him.

Korean horror/transgressive cinema received a boost when Park Chan-wook began his “Revenge Trilogy,” a trilogy of films dealing with revenge, its obsessive structure, and its consequences on identity. The three films feature stunning, original direction coupled with brutal violence, graphic sexuality, and intense psychological introspection. Chan-wook kicked off the trilogy with Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (2002), a tragic revenge tale of a deaf and mute man trying to purchase a black market kidney for his ailing sister. When he is screwed over, he devotes himself to brutal vengeance. But Park Chan-wook remains most famous for the middle entry in the series: Oldboy (2003), which

Korean horror/transgressive cinema received a boost when Park Chan-wook began his “Revenge Trilogy,” a trilogy of films dealing with revenge, its obsessive structure, and its consequences on identity. The three films feature stunning, original direction coupled with brutal violence, graphic sexuality, and intense psychological introspection. Chan-wook kicked off the trilogy with Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (2002), a tragic revenge tale of a deaf and mute man trying to purchase a black market kidney for his ailing sister. When he is screwed over, he devotes himself to brutal vengeance. But Park Chan-wook remains most famous for the middle entry in the series: Oldboy (2003), which won the grand prix at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival. Based on the manga of the same name, Oldboy concerns an alcoholic man who suddenly is kidnapped and imprisoned for fifteen years. But this is no ordinary prison; instead, it is a company that accepts money to kidnap and keep people captive in apartments for predetermined periods of time. During a night of drunken debauchery, Oh Dae-Su is abducted and placed in a furnished hotel room for fifteen years. His captors feed him, bathe him, give him drugs to keep him sane during his incarceration, and tend to his wounds after

won the grand prix at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival. Based on the manga of the same name, Oldboy concerns an alcoholic man who suddenly is kidnapped and imprisoned for fifteen years. But this is no ordinary prison; instead, it is a company that accepts money to kidnap and keep people captive in apartments for predetermined periods of time. During a night of drunken debauchery, Oh Dae-Su is abducted and placed in a furnished hotel room for fifteen years. His captors feed him, bathe him, give him drugs to keep him sane during his incarceration, and tend to his wounds after  his repeated suicide attempts. Over the course of the fifteen years, Oh Dae-Su’s only companion and connection to the outside world is the television in his room from which he witnesses a decade and a half of history including the rise of Kim Jong Il to power in the North Korea and the collapse of World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. After he is finally released, the bulk of the film

his repeated suicide attempts. Over the course of the fifteen years, Oh Dae-Su’s only companion and connection to the outside world is the television in his room from which he witnesses a decade and a half of history including the rise of Kim Jong Il to power in the North Korea and the collapse of World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. After he is finally released, the bulk of the film  follows Oh Dae-Su’s quest for revenge and explores how revenge begins to replace our identities. Featuring scenes of torture, horrific violence, graphic and taboo-stretching sexuality, stylish direction, and brilliant acting, Oldboy

follows Oh Dae-Su’s quest for revenge and explores how revenge begins to replace our identities. Featuring scenes of torture, horrific violence, graphic and taboo-stretching sexuality, stylish direction, and brilliant acting, Oldboy  depicts the kind of deep suffering that can lie at the heart of human identity and the manner in which our past can efface our present. I will not give away the rest of Oldboy’s plot, but I guarantee that it is cinematic experience you will not forget. From its philosophical pondering to its visceral torture scenes to its shocking revelations, Oldboy remains one of the most original and memorable films of the 21st century so far. Chan-wook rounded out his trilogy with Sympathy for

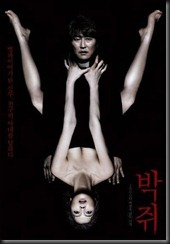

depicts the kind of deep suffering that can lie at the heart of human identity and the manner in which our past can efface our present. I will not give away the rest of Oldboy’s plot, but I guarantee that it is cinematic experience you will not forget. From its philosophical pondering to its visceral torture scenes to its shocking revelations, Oldboy remains one of the most original and memorable films of the 21st century so far. Chan-wook rounded out his trilogy with Sympathy for Lady Vengeance (2005), which tells the tale of a young woman who is falsely imprisoned for murder and seeks revenge upon her release. After completing the “Vengeance Trilogy,” Park Chan-wook went on to make his own take on the vampire genre, Thirst (2009), which concerns a priest who is transformed into a vampire and the love he develops for a young woman. With the “Vengeance Trilogy” and Thirst, Park Chan-wook has emerged as one of the most original, powerful, and visceral directors of the last decade, and he has helped to solidify Asian cinema’s place in the annals of great horror/transgressive cinema.

Lady Vengeance (2005), which tells the tale of a young woman who is falsely imprisoned for murder and seeks revenge upon her release. After completing the “Vengeance Trilogy,” Park Chan-wook went on to make his own take on the vampire genre, Thirst (2009), which concerns a priest who is transformed into a vampire and the love he develops for a young woman. With the “Vengeance Trilogy” and Thirst, Park Chan-wook has emerged as one of the most original, powerful, and visceral directors of the last decade, and he has helped to solidify Asian cinema’s place in the annals of great horror/transgressive cinema.

One of the most famous scenes from Oldboy, this fight scene features Oh Dae-Su battling an entire gang of thugs. For the bulk of the scene, Park Chan-Wook keeps the camera at a 90-degree angle to the action in order to give the appearance of an old-style, side-scrolling video game.