Here it is: the first part of the lost slasher posting that attempts to provide a basic outline of slasher and serial killer cinema. I will posting it in three parts: precursors, the golden age of slasher films, and slasher and serial killer cinema from the 1990s onwards. This series of posts also features a soundtrack of sorts—I have posted videos of these songs. You can watch them as videos or play them as a soundtrack while reading the post. The songs range widely in genre from folk (Bruce Springsteen and Sufjan Stevens) to punk (The Misfits) to post-punk/new wave (The Talking Heads) to alternative (They Might Be Giants) to metal (Rob Zombie).

For starters, for those of you who are too young or do not listen to weird enough music to get my title’s allusion…..

Post-punk, new wave pioneers The Talking Heads’ classic “Psycho Killer.”

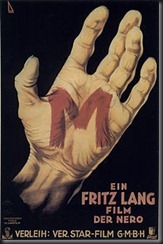

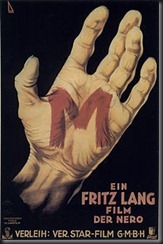

The roots of serial killer cinema can be traced all the way back to Fritz Lang’s 1931 masterpiece M. Already recognized as a master stylist for his silent films like Dr. Mabuse: Gambler (1922), Die Nibelungen (1924), and Metropolis (1927), German filmmaker Fritz Lang moved into the realm of sound cinema with the release of M. Lang had also demonstrated himself to be one of the first great masters of genre cinema with his two-part adaptation of the epic poem Nibelungenlied and his science fiction

The roots of serial killer cinema can be traced all the way back to Fritz Lang’s 1931 masterpiece M. Already recognized as a master stylist for his silent films like Dr. Mabuse: Gambler (1922), Die Nibelungen (1924), and Metropolis (1927), German filmmaker Fritz Lang moved into the realm of sound cinema with the release of M. Lang had also demonstrated himself to be one of the first great masters of genre cinema with his two-part adaptation of the epic poem Nibelungenlied and his science fiction  masterpiece Metropolis. With M, he moved into the world of serial killer horror. Starring the great Peter Lorre (Casablanca, The Maltese Falcon) as a child murderer, M follows the actions of the killer as well as the attempts by the police and the

masterpiece Metropolis. With M, he moved into the world of serial killer horror. Starring the great Peter Lorre (Casablanca, The Maltese Falcon) as a child murderer, M follows the actions of the killer as well as the attempts by the police and the  criminal gangs of the city to find the killer. Because the police prove incapable of capturing the killer, the organized crime bosses of the city take it upon themselves to bring this evildoer to justice before more of their own children die. A film that is as heartbreaking as it is horrifying, M is a powerful early cinematic depiction of insanity and society’s inability to grapple with the mentally ill that continues to rank high on any list of the greatest films of all time.

criminal gangs of the city to find the killer. Because the police prove incapable of capturing the killer, the organized crime bosses of the city take it upon themselves to bring this evildoer to justice before more of their own children die. A film that is as heartbreaking as it is horrifying, M is a powerful early cinematic depiction of insanity and society’s inability to grapple with the mentally ill that continues to rank high on any list of the greatest films of all time.

The opening of Fritz Lang’s classic M, which featured creepy children’s rhymes long before A Nightmare on Elm Street.

Serial killer cinema did not make a profound reappearance until 1960, which saw the release of two classics that changed the shape of horror cinema: Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho and Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom. As we discussed in class, Psycho fundamentally changed the shape of horror cinema with its (for the time) graphic depictions of murder, perversion, and insanity. Already well-versed in films about murder (Spellbound [1945], Rope [1948], Strangers on a Train [1951], Dial M for Murder [1954], Rear Window [1954], Vertigo [1958], etc.), Psycho reached new heights of the macabre with its infamous shower scene that

Serial killer cinema did not make a profound reappearance until 1960, which saw the release of two classics that changed the shape of horror cinema: Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho and Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom. As we discussed in class, Psycho fundamentally changed the shape of horror cinema with its (for the time) graphic depictions of murder, perversion, and insanity. Already well-versed in films about murder (Spellbound [1945], Rope [1948], Strangers on a Train [1951], Dial M for Murder [1954], Rear Window [1954], Vertigo [1958], etc.), Psycho reached new heights of the macabre with its infamous shower scene that  depicted more of a naked woman being cut up than any film previously. In fact, all films that feature beautiful women being cut up that came after could in sense be said to be remaking Hitckcock’s iconic scene. Since we discussed Psycho in class, I will not dwell upon its merits, but instead point to an equally provocative film that was released the same year across the Atlantic in Great Britain. Reviled by critics upon its release, Peeping Tom essentially ruined the career of director Michael Powell because of its bold, controversial subject matter. Peeping Tom follows a young man who works on a film crew and aspires to become a director. He also makes extra money making pornographic pictures and films for a local film developer. And, in between his two jobs, he stalks and kills women while filming them. Stylish, disturbing, and brutal, Peeping Tom probably transgresses even more boundaries than Psycho with its depictions of prostitutes and pornography that even included brief nudity,

depicted more of a naked woman being cut up than any film previously. In fact, all films that feature beautiful women being cut up that came after could in sense be said to be remaking Hitckcock’s iconic scene. Since we discussed Psycho in class, I will not dwell upon its merits, but instead point to an equally provocative film that was released the same year across the Atlantic in Great Britain. Reviled by critics upon its release, Peeping Tom essentially ruined the career of director Michael Powell because of its bold, controversial subject matter. Peeping Tom follows a young man who works on a film crew and aspires to become a director. He also makes extra money making pornographic pictures and films for a local film developer. And, in between his two jobs, he stalks and kills women while filming them. Stylish, disturbing, and brutal, Peeping Tom probably transgresses even more boundaries than Psycho with its depictions of prostitutes and pornography that even included brief nudity,  but it remains unknown except to film enthusiasts because it was so despised upon its release that it never developed a popular following. Again, like Psycho, Peeping Tom is a profoundly Freudian film about the effects of childhood trauma upon the development of adulthood fixations, perversions, and neuroses. An insightful exploration of identity and our connection to the Other, Peeping Tom examinations the nature of terror and voyeurism as well as our need for the Other to shore up our conceptualization of our selves. For without the Other, without the

but it remains unknown except to film enthusiasts because it was so despised upon its release that it never developed a popular following. Again, like Psycho, Peeping Tom is a profoundly Freudian film about the effects of childhood trauma upon the development of adulthood fixations, perversions, and neuroses. An insightful exploration of identity and our connection to the Other, Peeping Tom examinations the nature of terror and voyeurism as well as our need for the Other to shore up our conceptualization of our selves. For without the Other, without the  Other’s desire for us (or terror of us if we are a particular brand of pervert), then how are we to define and validate our own identities? Love, as psychoanalysis reminds us, always remains narcissistic at its core, and the same can be seen in such psychotic forms of behavior in which the terror of the subject narcissistically reflects the psycho or pervert back to himself. It is a perverted carry-over of the Lacanian mirror stage into adulthood, and it is no accident that the eponymous peeping tom using mirrors to further terrify his victims.

Other’s desire for us (or terror of us if we are a particular brand of pervert), then how are we to define and validate our own identities? Love, as psychoanalysis reminds us, always remains narcissistic at its core, and the same can be seen in such psychotic forms of behavior in which the terror of the subject narcissistically reflects the psycho or pervert back to himself. It is a perverted carry-over of the Lacanian mirror stage into adulthood, and it is no accident that the eponymous peeping tom using mirrors to further terrify his victims.

The opening scene of Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom, which establishes the brutal, voyeuristic style of the film from its very first seconds.

The Misfits’ punk classic “Horror Business” that was inspired by Hitchcock’s Psycho—The Misfits regularly wrote songs inspired by horror films: “You don’t go in the bathroom with me / Or with you / I’ll put a knife right in you.” Talk about poetry!!!! Plus, “We are 138” is thrown in for good measure….

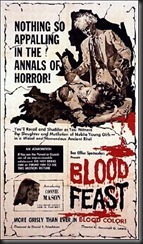

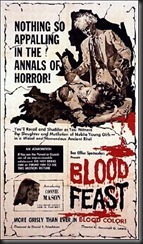

The 1960s also saw the rise of a sub-genre of horror that would directly influence the slasher and serial killer cinema in the decades to come. This bloody, low-budget genre known as “splatter” was epitomized by the films of Herschell Gordon Lewis, particularly his so-called “Blood Trilogy”: Bloody Feast (1963), Two Thousand Maniacs (1964), and Color Me Blood Red (1965). Lewis was a filmmaker who specialized in nudie films, softcore films that generally featured almost no plot and centered around nudists cavorting around with one another. But Lewis moved from such sexploitative fare into more horror-centered exploitation; however, he never really developed complex plots, good writing, or believable acting to speak of. Instead, his films are almost purely centered around the bloody spectacles that he pioneered. Perhaps now most famous as the director that Ellen Page and Jason Bateman watch together in Juno (2007), Lewis made a career out of villains who enjoy eviscerating people and then playing gleefully with their innards. His films look like they were made for ten bucks by a child, and

The 1960s also saw the rise of a sub-genre of horror that would directly influence the slasher and serial killer cinema in the decades to come. This bloody, low-budget genre known as “splatter” was epitomized by the films of Herschell Gordon Lewis, particularly his so-called “Blood Trilogy”: Bloody Feast (1963), Two Thousand Maniacs (1964), and Color Me Blood Red (1965). Lewis was a filmmaker who specialized in nudie films, softcore films that generally featured almost no plot and centered around nudists cavorting around with one another. But Lewis moved from such sexploitative fare into more horror-centered exploitation; however, he never really developed complex plots, good writing, or believable acting to speak of. Instead, his films are almost purely centered around the bloody spectacles that he pioneered. Perhaps now most famous as the director that Ellen Page and Jason Bateman watch together in Juno (2007), Lewis made a career out of villains who enjoy eviscerating people and then playing gleefully with their innards. His films look like they were made for ten bucks by a child, and  they feature acting that makes porn films look like Citizen Kane. Lewis’s “Blood Trilogy” began with Blood Feast, which concerns an caterer obsessed with Egyptian cannibalistic feasts. Lewis continued the trilogy with Two Thousand Maniacs, the tale of a small Southern town that lures in a group of unsuspecting Yankees in order to ritualistically slaughter them in remembrance of their town falling to the Union army. Finally, he rounded out the trilogy with Color Me Blood Red, a kunstlerroman of sorts (that’s a joke) about a painter who decides to improve his style by killing people and incorporating their blood into his paintings. Lewis made other splatter classics as well, such as The Wizard of Gore (1970) that tells the story of a magician who

they feature acting that makes porn films look like Citizen Kane. Lewis’s “Blood Trilogy” began with Blood Feast, which concerns an caterer obsessed with Egyptian cannibalistic feasts. Lewis continued the trilogy with Two Thousand Maniacs, the tale of a small Southern town that lures in a group of unsuspecting Yankees in order to ritualistically slaughter them in remembrance of their town falling to the Union army. Finally, he rounded out the trilogy with Color Me Blood Red, a kunstlerroman of sorts (that’s a joke) about a painter who decides to improve his style by killing people and incorporating their blood into his paintings. Lewis made other splatter classics as well, such as The Wizard of Gore (1970) that tells the story of a magician who  performs illusions of women being murdered and dismembered onstage. The catch is that they fall apart and die in similar ways later on once the performance is over—this is the film that appears briefly in Juno. Other Lewis films included The Gore Gore Girls (1972), which concerns a killer that targets Go Go Girls (girls paid to dance at clubs; although they are basically strippers in the films) and A Taste of Blood (1967), a craptastic and bloody-as-hell vampire tale. Lewis’ legacy is not necessarily a noble one—he cannot even remotely be compared to the previous directors in this posting. His films would appear direct-to-video were they released today, but he remains a beloved and highly influential figure in the history of horror, cult, and exploitation cinema.

performs illusions of women being murdered and dismembered onstage. The catch is that they fall apart and die in similar ways later on once the performance is over—this is the film that appears briefly in Juno. Other Lewis films included The Gore Gore Girls (1972), which concerns a killer that targets Go Go Girls (girls paid to dance at clubs; although they are basically strippers in the films) and A Taste of Blood (1967), a craptastic and bloody-as-hell vampire tale. Lewis’ legacy is not necessarily a noble one—he cannot even remotely be compared to the previous directors in this posting. His films would appear direct-to-video were they released today, but he remains a beloved and highly influential figure in the history of horror, cult, and exploitation cinema.

Trailer for Lewis’s Blood Feast

Trailer for Lewis’s The Wizard of Gore—features graphic mutilation.

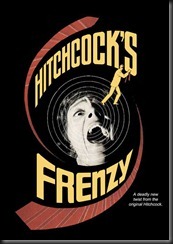

Hitchcock returned to Britain and the serial killer genre with 1972’s Frenzy, a film that demonstrates how horror cinema had changed over the course of the 1960s. While Psycho was hyper-transgressive for its time but appears slightly tame by today’s standards, Frenzy eschews such subtleties in its depiction of graphic strangulations and full-frontal nudity. The film shows way more than Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom did ten years earlier but was not met with revulsion because of society’s steadily evolving desensitization towards such plot elements. Frenzy follows an unemployed, divorced bartender who becomes the police’s prime suspect in a series of serial strangulations. The killer strangles his victims with neckties, which are found around their necks when the bodies are discovered. However, we—the audience—know who the killer is for the bulk of the film because Hitchcock depicts the murders. Hence, we follow both sides of the action, and the bulk of the film’s tension derives from us wondering whether said bartender will find the evidence to exonerate himself or whether he will be convicted for a series of brutal crimes that we know he did not commit.

SPOILER ALERT: One of the murder scenes from the film in which Hitchcock chooses to have his camera drift around in an almost disembodied fashion instead of depicting the crime.

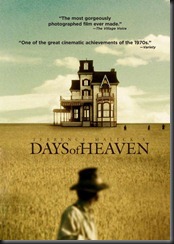

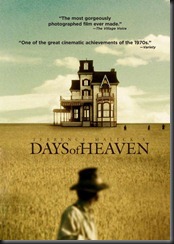

Finally, I will close by discussing probably the quietest film on this list. The real life murder spree of Charles Starkweather and his teenage girlfriend Caril Ann Fugate has become a cultural text that has, inspired numerous takes on the story, the first of which was visionary auteur Terrence Malick’s first film Badlands (1973). Malick has become one of the most visionary, acclaimed, and enigmatic directors of the past forty years—he once went almost twenty years without releasing a film. Badlands establishes many of his trademark stylistic touches and themes. One should never mistake the main characters of a Malick film as the focus of his narratives; instead, nature is always the central character of Malick’s films. His films are perhaps even more naturalistic than the novels of the classic naturalists like Zola and Steinbeck because

themes. One should never mistake the main characters of a Malick film as the focus of his narratives; instead, nature is always the central character of Malick’s films. His films are perhaps even more naturalistic than the novels of the classic naturalists like Zola and Steinbeck because  the camera enables him to actually focus upon the environment that shapes the characters’ actions. Influenced by Darwinism and Marxism, naturalism sees humans as the products of various environmental and socio-economic forces that shape our identities and ultimately determine the paths we follow. Naturalism reintroduces the idea of fate from Greek tragedy, but it is no longer the effect of the gods—it is the effect of biology, environment, politics, and economy. Badlands begins to develop these themes that will become so prominent

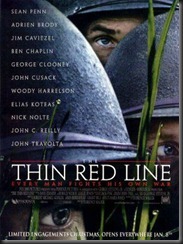

the camera enables him to actually focus upon the environment that shapes the characters’ actions. Influenced by Darwinism and Marxism, naturalism sees humans as the products of various environmental and socio-economic forces that shape our identities and ultimately determine the paths we follow. Naturalism reintroduces the idea of fate from Greek tragedy, but it is no longer the effect of the gods—it is the effect of biology, environment, politics, and economy. Badlands begins to develop these themes that will become so prominent in later Malick masterpieces like Days of Heaven (1978) and The Thin Red Line (1998). Featuring an extremely young Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek, the film follows the pair as they become romantically involved with one another and then proceed on a cross-country murder spree. Malick’s film is never judgmental, and each crime arises as a natural progression from the situation within which the characters find themselves. The couple at one point retreat to the woods

in later Malick masterpieces like Days of Heaven (1978) and The Thin Red Line (1998). Featuring an extremely young Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek, the film follows the pair as they become romantically involved with one another and then proceed on a cross-country murder spree. Malick’s film is never judgmental, and each crime arises as a natural progression from the situation within which the characters find themselves. The couple at one point retreat to the woods  where they live a blissfully utopian existence until society finds them again. And ultimately they end up in the badlands of Montana, a terrain that seems as inhospitable to humans as its name implies. If you’ve never driven through Montana in person, then you have no idea what’s it really like—and driving through there is fun because you can drive as fast as you want. Malick never glorifies the murders nor does he condemn them—they happen like a tiger killing a gazelle in a nature video. If you have never seen a Malick film, Badlands is a great staring place because it is much shorter than his subsequent films. It introduces you to his meditative style and naturalistic aesthetic but without the attention span required for his later films. Look for Malick’s new film, The Tree of Life, which is hitting theaters at the end of May.

where they live a blissfully utopian existence until society finds them again. And ultimately they end up in the badlands of Montana, a terrain that seems as inhospitable to humans as its name implies. If you’ve never driven through Montana in person, then you have no idea what’s it really like—and driving through there is fun because you can drive as fast as you want. Malick never glorifies the murders nor does he condemn them—they happen like a tiger killing a gazelle in a nature video. If you have never seen a Malick film, Badlands is a great staring place because it is much shorter than his subsequent films. It introduces you to his meditative style and naturalistic aesthetic but without the attention span required for his later films. Look for Malick’s new film, The Tree of Life, which is hitting theaters at the end of May.

Next time, I will begin to discuss the birth of the actual slasher film, but for now, I leave you with Bruce Springsteen’s take on the Starkweather murders that inspired Badlands….

The opening, eponymous track of Bruce Springsteen’s classic album Nebraska tells the tale of Starkweather in heartbreaking (and probably romanticized) terms. One of my all time favorites.

No comments:

Post a Comment