Tuesday, April 26, 2011

Psycho: The True Story

Recent female characters

Female characters in our recent movies

Night of the Living Dead - Zombie Commies again!!

Nightmare on Elm Street. - Freddy likes girls more than boys

Monday, April 25, 2011

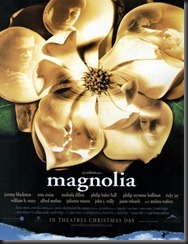

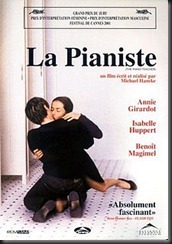

AL’s Weekly Blog Post #13: Emotional Glaciation; or, the Cinema of Michael Haneke

Haneke’s most recent film, The White Ribbon (2009), was his first black and white film and his first to win the Palm d’Or at The Cannes Film Festival. A hauntingly beautiful and disturbing depiction of a German village on the cusp of World War I, the film concerns the puritanical education of the village’s children and their often inhumane punishment. On a more general level, it concerns the disturbing and violent events that are occurring beneath the seemingly placid,

The same year as The White Ribbon also saw the release of an absurdist Greek drama that participates in a similar style to Haneke. Yorgos Lanthimos’s Kynodontas (2009; Dogtooth) concerns a family that has kept its three, now adult children from the outside world—they are not allowed to travel beyond their house’s gates until they have lost their dogteeth. The parents have taught their children that words means different things than they do in reality, and the father pays a young woman from work to come into the house and have sex with the son. A powerful

Sunday, April 24, 2011

Nightmare on Elm Street

Inspired by True Events??? Really?

“Inspired by true events” is a phrase commonly seen at the beginning of serial killer flicks. But, I always wonder just how “true” these events are? I think the phrase can often be misleading, but it ultimately makes the audience’s experience scarier knowing that these things could have happened like this in the real world. The serial killer Ed Gein provided inspiration for the leading creeps in “Psycho,” “Texas Chainsaw Massacre,” and “Silence of the Lambs.” Only small details from Ed Gein’s horrific murders are used as inspiration. In the case of “Texas Chainsaw Massacre,” the special edition DVD of the remake has a very interesting documentary-like spill in the special features all about Gein and his killing spree in Wisconsin.

“The Strangers” (2008) is a newer film that is “based on true events” but these events are disappointing when you consider the horrific actions in the movie. For those of you who have not seen it, “The Strangers” follows a couple, on the rocks, who stops to stay the night at a cabin on the way back from a friend’s wedding. Upon arriving, they are greeted and ultimately tortured by strangers. The scariest part of this film (at least for me) is that the killers have no motive at all, just boredom. Also, the entire movie is built on suspense. The killers parole the perimeter of the house (and sometimes the inside of the house) and leave creepy messages on the doors and windows. After I saw this movie, I immediately started searching for the story that inspired the plot. I was disappointed to find that the film was based partly on the Manson murders, 1981 Kedie Cabin killings in Sierra Nevada’s, and partly on an “event” that happened to the director as a kid.

“As a kid, I lived in a house on a street in the middle of nowhere. One night, while our parents were out, somebody knocked on the front door and my little sister answered it. At the door were some people asking for somebody who didn't live there. We later found out that these people were knocking on doors on the area and, if no one was home, breaking into the houses,” – Bryan Bertino, director.

These scary real-life stories have been made into some terrifying films over the years. However, it still bothers me how loosely directors throw around "inspired by true events” or “based on a true story.” How can they honestly put these labels on films that are basically straight fiction? My verdict is that it just straight up makes the movies scarier when you know they are “real.”

Saturday, April 23, 2011

Nightmares

Thursday, April 21, 2011

Funny Games

Sunday, April 17, 2011

Slasher films

I suppose these movies seem more real to me than science fiction or zombie thrillers that contain more obviously fantastical creatures that are known not to exist, rather than a normal human whose psychological processing has been interrupted by some traumatic but plausible event that has caused them to respond with a gruesome rampage. Perhaps these films engage with some of our deepest, most twisted fears in order to convince us that such sick individuals are out there and perhaps just a step away with every creak in our homes and rustle in the bushes.

Black Christmas

Suspense in Black Christmas

The film also combines a series of claustrophobic shots, especially when introducing the killer. Clark films him in fragments to add mystery to his character and reveal his fragmented mind. We never see his face completely, but instead we're often trapped in his point of view, which often originates in a closet or a tight space. While the drama unfolds at night, adding an even greater sense of foreboding, Clark uses every angle and inch of space in his shots to conjure suspense and surprise.

This was the first film all semester where I truly felt on the edge of my seat and surprised by what was to come. A movie about a serial killer in a sorority house could have been painfully predictable, but I think Clark's techniques in creating suspense and anxiety among viewers is genius.

1, 2 Freddy's Coming for You

Ironically, what I find most evil about Freddy is his sense of humor. He is truly sadistic and not a homicidal child trapped in a man's body or a gender confused Oedipal character. His humor shows his true joy in killing and torturing his victims. We've already seen him take one victims life, but this is yet the first to come. In that first killing sequence we saw both his sheer viciousness and his comedic taunting of his victim just for the sake of seeing him or her in fear. Freddy is evil. Freddy is the boogeyman.

Saturday, April 16, 2011

Psycho and Taboos

That being said, Psycho is as classic a film today as it was edgy for the time. I’ve seen a number of Hitchcock films but I cannot recall in any of them the female characters walking around half-dressed or lying in bed with their boyfriends. The film can be dated by the language and elements that were seen as “racy” at the time. You don’t ever see Janet Leigh’s navel- that would have been a no-no until I Love Jeannie eventually forced the taboo out. I even discovered through the magic of the Internet that the flushing of the toilet was even taboo at the time.

I wasn’t familiar with the “sequels” to the Psycho film until Wikipedia directed me to them. In these sequels Anthony Perkins return as Norman Bates, commits more murders, but all because “Mother” has come back into his psyche and taken over. The sequels, instead of incriminating Bates, try to make the audience sympathize with him. Perhaps in the decades that followed the original, when the sequels were made, there was not only a greater understanding of mental illness but sympathy for people with those conditions.

Night of the Living Dead and Race

Psycho and Slasher Film

Any slasher film that preys on the idea of when the real life audience are the most vulnerable have a higher chance of actually being terrifying compared to those that continuously put a group of kids in the woods only to be chopped up by some deranged and child abused killer. When done the right way, a small scene that targets our most basic fears (killer under the bed, noises in the house)are the biggest nightmare to the audience because they start out with an element of the unknown. The fact that the first viewing audiences of Psycho did not know that Norman was both the killer and his mother was doubly terrifying because it forced them to deal with the idea that a normal perception of behavior could also serve as a phsychotic one. That we may never know the type of people we actually surround ourselves with. Those slasher films that can leave the audience still questioning after the film will always be transcendent of the rest.

Slasher Films and Psycho

As I’ve stated in earlier posts, the horror genre has never been high on my list due to its generally graphic content and its dependency on fright as its primary entertainment value. Nonetheless, as we progress through this section of the class I am finding less and less trepidation when it comes to several of these films. Take, for instance, the subcategory of slasher films. Despite their gory nature, I have come to find them quite predictable due to the limited realm of deathly techniques at the killer’s disposal. Additionally, there is often a comical nature associated with the characters, as though the characters know of their impending doom and the director is making morbid jokes about their inability to survive. In fact, the latest Scream sequel’s television trailer boasts that the film is “hilarious” among other adjectives describing the horrific elements of the film.

I had a similar impression when watching the original cut of Psycho for the first time. As with many of the early films we have watched, the film is comical in what it considers racy, which is almost G-rated in today’s society. However, placing myself in the timing of the film’s release, I can understand how it has developed into a timeless classic. The plot of the movie is genius in the fact that it throws viewers off by killing off the supposed protagonist midway through the film. This throws off the audience to think that perhaps the prior 40 minutes of plot were meaningless.

Additionally, Hitchcock focuses on the psyche of the murderer rather than his actual killings. Thus, the film succeeds where many modern slashers stumble. Rather than inundating viewers with graphic kill after graphic kill, the murderer only successfully kills two characters off during the movie. Nonetheless, by developing the insanity of the character, Hitchcock develops a much scarier character than any mass murderer. The audience sees how and why the killer is so disturbed, earning him empathy and an element of realism. Instead of killing him off at the end of the film, Hitchcock allows the insanity to end the film. Thus, rather than feeling safe and secure that the killer is dead and out of their minds, Psycho’s audience is left to dwell on the madness of the killer and to cope with the understanding that insanity of that nature could exist in the real world.

Killer Clowns and Skull Ashtrays

...and Ed Gein (caught in the late '50s), who was probably Wisconsin's most notorious serial killer before Jeffrey Dahmer came along in the '90s. Here's a short documentary about Ed, who was part of Hitchcock's inspiration for Psycho. Ed, who also had mommy issues, used to gut people like deer and use their skins and skulls to make furniture, lampshades, ashtrays, etc. He was handy like that.

I'm not sure how familiar people are with Jeffrey Dahmer anymore, but he started murdering folks in the '70s and wasn't caught until the mid '90s. He lived in my hometown, frequented a couple of the same bars I used to go to, and looked creepily familiar when I first saw his picture on the news. My best friend's dad was one of the cops on the scene when the remains of his victims were found in the guy's apartment. The stench was unbearable, and he has no idea why the neighbors never complained.

So anyway, my point is that serial killers are something you hear about all the time, so they pack the biggest scare punch for me. This film from 1990, Henry:Portrait of a Serial Killer, is probably one of the most realistic, frightening, and well-made serial killer films you'll ever see:

I saw it at a 10pm showing when it came out, and I had to walk home alone afterward, which was very poor planning indeed.

On a lighter note, here are trailers from a couple of my all-time favorite deranged killer B-movies. Both are brilliant.

In Two Thousand Maniacs! (1964) some young Yankee travelers are lured into a southern small town that isn't always there, and the townspeople convince them to join them for a centennial celebration they are throwing. Then the Yanks are all killed one-by-one in extremely inventive ways--some of which include festival games that the whole town participates in. It is awesome and has the best soundtrack since Lawrence of Arabia.

In Spider Baby (1968), distant relatives come to visit three orphaned children who are being cared for by the family chauffeur (played by Lon Chaney Jr.). The kids have some weird disease that causes evolutionary regression. Gore ensues.

Oh...and on a lighter lighter note, here's my all-time favorite black comedy, Parents (1989), in which a kid in a seemingly idyllic 1950s family learns that his parents are extremely twisted individuals.

Sleep tight, all.

Psycho shower

Alfred Hitchcock’s “Pyscho” was one of the best horror films I have seen in a very long time. It had everything a movie of this genre should have; there was gore in the shower, an interesting plot line, and a great twist at the end. It kept me on the edge of my seat the entire movie. I have to say the shower scene was one of the greatest murder scenes I have seen in a horror film. You already felt very creeped out because Norman was watching her undress through his hole in the wall. Then, as you suspect that maybe everything will be alright, the creepy shadow appears from behind the curtain, further incriminating his “mother.” The blood being in black and white was much more believable than most color films I have seen. All of the chunks that you see floating down the drain were more than enough to make me feel queasy. After watching this film I felt afraid to take a shower for a few days, I locked my door to make sure no murdering mothers would enter.

Unfulfilling Christmas

That being said, the movie was so-so. It was quite corny but it definitely had its moments of shock value. The relationship between Jess and her boyfriend was a well-thought-out commentary on the progressive role of women during this era, but again I was disappointed that it concluded so senselessly. Aside from the progressive social commentary which I give this movie credit for, I really didn't enjoy how unrealistic it was. Slasher films have never been on the top of my list for this reason. Stupid, irrational characters just make me angry and annoyed because I know that people are not quite that dumb in real life. I like some realism in my films!

Black Christmas:

I have to admit that I was expecting for the women in Black Christmas to be shown in an even worse light than perhaps they were. Not sure why, but when I saw that the movie was going to take place in a sorority house I expected for the girls to be shown running around in their underwear, having pillow fights, and having sex with their boyfriends. Instead the girls kept their close on, yes they drank a lot but I almost felt that was a statement about the time. I saw the movie as showing what they believed college life was like at the time. The students were shown as drinking heavily and there is no mention of going to class or taking exams (even though it was close to the holiday). I was even impressed with the posters that were shown in the girl’s room. The posters had nudity and I found this extremely funny because most people would see that as “un-lady like”.