This past week’s films stem from two distinctive national cinemas: British and Italian. Both Nicolas Roeg and Italian horror cinema generated powerful new horror aesthetics that continue to influence horror films up until the present day. Hence, in this week’s post, I want to briefly discuss the films of Nicolas Roeg including a discussion of the psychoanalytical themes of Don’t Look Now. Then, I will proceed to provide a thumbnail sketch of Italian horror, which broke new ground in terms of visceral content and laid the foundation for the slasher film.

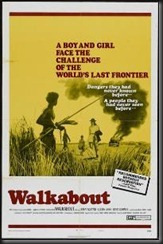

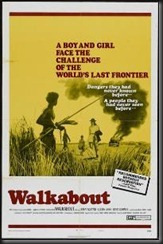

While British director Nicolas Roeg’s filmography as a director may not seem extensive for someone who has worked in the film industry for forty years, he nonetheless created some of the most distinctive, powerful, and introspective British films of the 1970s and proved himself to be a director capable of playing with genres like science fiction and horror in ways that expanded them in radically new directions. Roeg’s first film was a thriller entitled Walkabout (1971). Walkabout begins with an inexplicably horrific moment: a father is driving his son and daughter across the Australian outback, he stops the car for a picnic, and

While British director Nicolas Roeg’s filmography as a director may not seem extensive for someone who has worked in the film industry for forty years, he nonetheless created some of the most distinctive, powerful, and introspective British films of the 1970s and proved himself to be a director capable of playing with genres like science fiction and horror in ways that expanded them in radically new directions. Roeg’s first film was a thriller entitled Walkabout (1971). Walkabout begins with an inexplicably horrific moment: a father is driving his son and daughter across the Australian outback, he stops the car for a picnic, and then he suddenly begins shooting at them for no apparent reason. They hide from him, so—of course—he sets fire to their car and then commits suicide. The rest of the film follows the young duo’s attempt to navigate their way back home across the wild and brutal terrain. A bildungsroman of sorts, Walkabout is also an existential fable about identity in the postmodern world and the conflict between natural and urban environments. Roeg followed up Walkabout with the surrealistic, meditative horror film Don’t Look Now (1973), which we watched for class and which remains one of the greatest art-horror films of all time. Don’t Look Now follows a couple (Donald Sutherland and

then he suddenly begins shooting at them for no apparent reason. They hide from him, so—of course—he sets fire to their car and then commits suicide. The rest of the film follows the young duo’s attempt to navigate their way back home across the wild and brutal terrain. A bildungsroman of sorts, Walkabout is also an existential fable about identity in the postmodern world and the conflict between natural and urban environments. Roeg followed up Walkabout with the surrealistic, meditative horror film Don’t Look Now (1973), which we watched for class and which remains one of the greatest art-horror films of all time. Don’t Look Now follows a couple (Donald Sutherland and  Julie Christie) whose young daughter dies in the opening montage of the film. Roeg’s film was highly controversial upon its release because of its lengthy and graphic (for the time) sex scene between Sutherland and Christie. A supernatural thriller, Don’t Look Now uses unconventional editing techniques, particularly Roeg’s elaborate usage of

Julie Christie) whose young daughter dies in the opening montage of the film. Roeg’s film was highly controversial upon its release because of its lengthy and graphic (for the time) sex scene between Sutherland and Christie. A supernatural thriller, Don’t Look Now uses unconventional editing techniques, particularly Roeg’s elaborate usage of  dialectical montage and abrupt cuts, and impressionistic imagery to explore the nature of grief. Profoundly psychological, Don’t Look Now plumbs the depths of the lack of being that French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan argues lies at the heart of all human desire. The couple come face to face with their individual lacks when their daughter drowns suddenly, and the film follows their attempts to, as psychoanalysis would call it, achieve a state of sublimation—they seek to fill their lack with substitute objects. Sutherland attempts to bury himself in his church restoration work and becomes obsessed with a small,

dialectical montage and abrupt cuts, and impressionistic imagery to explore the nature of grief. Profoundly psychological, Don’t Look Now plumbs the depths of the lack of being that French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan argues lies at the heart of all human desire. The couple come face to face with their individual lacks when their daughter drowns suddenly, and the film follows their attempts to, as psychoanalysis would call it, achieve a state of sublimation—they seek to fill their lack with substitute objects. Sutherland attempts to bury himself in his church restoration work and becomes obsessed with a small,  red-coated figure he keeps seeing around Venice that reminds him of the red-coat his daughter was wearing at the time of her death. Christie’s character becomes acquainted with a pair of sisters, one of whom claims she has received communications from the deceased daughter. The two also try to find sublimation in each other’s arms as the pair’s passionate lovemaking depicts them literally trying to fill the hole in their lives with each other’s bodies. The lengthy sex scene represents yet another spectacular moment of Roeg’s dialectical montage as he cuts back and forth between shots of the pair in bed to shots of them dressing and preparing for the

red-coated figure he keeps seeing around Venice that reminds him of the red-coat his daughter was wearing at the time of her death. Christie’s character becomes acquainted with a pair of sisters, one of whom claims she has received communications from the deceased daughter. The two also try to find sublimation in each other’s arms as the pair’s passionate lovemaking depicts them literally trying to fill the hole in their lives with each other’s bodies. The lengthy sex scene represents yet another spectacular moment of Roeg’s dialectical montage as he cuts back and forth between shots of the pair in bed to shots of them dressing and preparing for the  day, thus suggesting that sublimation found in sexual intercourse enables the couple to carry out their quotidian routines. After Don’t Look Now, Roeg proceeded to explore other genres. In 1975, Roeg released one of the great classics of science fiction cinema: The Man Who Fell to Earth, which starred musician—and frequent alien impersonator—David Bowie. Bowie plays Jerome Newton, an alien with a human appearance, who comes to Earth to devise a way of transporting water back to his home planet, which is undergoing a drought of apocalyptic proportions. While on Earth, he uses his advanced technological knowledge to begin creating

day, thus suggesting that sublimation found in sexual intercourse enables the couple to carry out their quotidian routines. After Don’t Look Now, Roeg proceeded to explore other genres. In 1975, Roeg released one of the great classics of science fiction cinema: The Man Who Fell to Earth, which starred musician—and frequent alien impersonator—David Bowie. Bowie plays Jerome Newton, an alien with a human appearance, who comes to Earth to devise a way of transporting water back to his home planet, which is undergoing a drought of apocalyptic proportions. While on Earth, he uses his advanced technological knowledge to begin creating  inventions that allow him to become the wealthy head of a multinational corporation. Newton becomes obsessed with watching television and sets up an entire wall of sets that he watches simultaneously. He also develops a relationship with an Earth woman and a fondness for alcohol. One of the strangest alien visitor films ever made, The Man Who Fell to Earth is a stylish meditation upon postmodern alienation and the desire to forge meaningful relationships. Roeg went on to create many more films, including Bad Timing (1980), which also featured a famous singer as the lead actor: Art Garfunkle of Simon and Garfunkle. In Bad Timing, Roeg also continued to pursue his fascination with using eroticism to explore psychological problems. However, it is Roeg’s initial three films that demonstrate his ability to blend arthouse stylistics with genres such as thrillers, horror, and science fiction.

inventions that allow him to become the wealthy head of a multinational corporation. Newton becomes obsessed with watching television and sets up an entire wall of sets that he watches simultaneously. He also develops a relationship with an Earth woman and a fondness for alcohol. One of the strangest alien visitor films ever made, The Man Who Fell to Earth is a stylish meditation upon postmodern alienation and the desire to forge meaningful relationships. Roeg went on to create many more films, including Bad Timing (1980), which also featured a famous singer as the lead actor: Art Garfunkle of Simon and Garfunkle. In Bad Timing, Roeg also continued to pursue his fascination with using eroticism to explore psychological problems. However, it is Roeg’s initial three films that demonstrate his ability to blend arthouse stylistics with genres such as thrillers, horror, and science fiction.

The original trailer for The Man Who Fell to Earth, which makes the film seem like an action-packed thriller instead of the cerebral drama that it actually is.

Roeg’s blending of genre films with arthouse cinema finds a parallel in the Italian horror films that began appearing in the 1950s. As our reading from Leon Hunt argues, certain Italian horror films represent “bad objects,” texts that blend seemingly irredeemable subject matter together with arthouse cinematic aesthetics. This blend of high and low creates a truly postmodern horror experience that blends visceral experiences together with the beautiful and sublime. The Italian film industry became a global cinematic force with the advent of Neorealism in the years

Roeg’s blending of genre films with arthouse cinema finds a parallel in the Italian horror films that began appearing in the 1950s. As our reading from Leon Hunt argues, certain Italian horror films represent “bad objects,” texts that blend seemingly irredeemable subject matter together with arthouse cinematic aesthetics. This blend of high and low creates a truly postmodern horror experience that blends visceral experiences together with the beautiful and sublime. The Italian film industry became a global cinematic force with the advent of Neorealism in the years  immediately following World War II. Directors like Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio de Sica, Federico Fellini, and Luchino Visconti created a national cinema that influences cinema up until the modern day. But Italian cinema did not really develop its

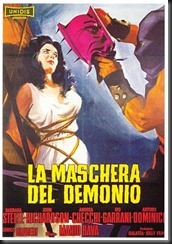

immediately following World War II. Directors like Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio de Sica, Federico Fellini, and Luchino Visconti created a national cinema that influences cinema up until the modern day. But Italian cinema did not really develop its  on take on horror cinema until the late 50s and early 60s with directors like Ricarrdo Freda and Mario Bava. The godfather of Italian horror cinema and one of the most influential horror directors of all time remains Mario Bava. While Bava produced classic films in a variety of different genres (fantasy, horror, action, science fiction, and westerns), he remains most famous for his horror films, particularly his stylish, gothic tales of the supernatural and his murder mystery (or giallo) films. In many ways

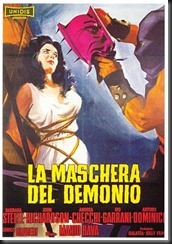

on take on horror cinema until the late 50s and early 60s with directors like Ricarrdo Freda and Mario Bava. The godfather of Italian horror cinema and one of the most influential horror directors of all time remains Mario Bava. While Bava produced classic films in a variety of different genres (fantasy, horror, action, science fiction, and westerns), he remains most famous for his horror films, particularly his stylish, gothic tales of the supernatural and his murder mystery (or giallo) films. In many ways , Italian horror can be said to begin with the release of Mario Bava’s The Mask of Satan (a.k.a. Black Sunday; 1960), a film that may seem tame by today’s standards but that remained banned in Britain for eight years following its release and was only released then in a severely edited format. Italian horror films featured graphic violence and open depictions of sexuality that were deemed inappropriate by most other world cinemas. Bava’s earlier films seem tame today, but they get increasingly extreme as the years progress, and they make American and British cinema of the time seem like children’s cartoons by comparison. In 1963, Mario Bava released what many consider to be the first giallo flim: The Girl Who Knew Too Much, which featured John Saxon who would become famous twenty years later as the father/police officer in Wes Craven’s A Nightmare on Elm

, Italian horror can be said to begin with the release of Mario Bava’s The Mask of Satan (a.k.a. Black Sunday; 1960), a film that may seem tame by today’s standards but that remained banned in Britain for eight years following its release and was only released then in a severely edited format. Italian horror films featured graphic violence and open depictions of sexuality that were deemed inappropriate by most other world cinemas. Bava’s earlier films seem tame today, but they get increasingly extreme as the years progress, and they make American and British cinema of the time seem like children’s cartoons by comparison. In 1963, Mario Bava released what many consider to be the first giallo flim: The Girl Who Knew Too Much, which featured John Saxon who would become famous twenty years later as the father/police officer in Wes Craven’s A Nightmare on Elm  St (1984). The Giallo is a peculiarly Italian hybrid genre that blends elements of the horror, mystery, and detective genres. Giallo literally means “yellow,” and it received its name from the trademark yellow colors of the often lurid Italian detective and crime fiction novels. The giallo mixes elements of detective fiction, murder mysteries, horror films, and sexploitation

St (1984). The Giallo is a peculiarly Italian hybrid genre that blends elements of the horror, mystery, and detective genres. Giallo literally means “yellow,” and it received its name from the trademark yellow colors of the often lurid Italian detective and crime fiction novels. The giallo mixes elements of detective fiction, murder mysteries, horror films, and sexploitation  together into a bizarre gestalt that must be experienced to be truly understood. While some claim The Girl Who Knew Too Much serves as the first example of the giallo, it remains a little too comical and upbeat to sit easily alongside successors in the genre. Instead, it is really Bava’s Blood and Black Lace (1964) that—for me, at least—represents the first truly distinctive example of the giallo film. Blood and Black Lace takes place

together into a bizarre gestalt that must be experienced to be truly understood. While some claim The Girl Who Knew Too Much serves as the first example of the giallo, it remains a little too comical and upbeat to sit easily alongside successors in the genre. Instead, it is really Bava’s Blood and Black Lace (1964) that—for me, at least—represents the first truly distinctive example of the giallo film. Blood and Black Lace takes place  at a fashion house, where the models begin being killed off one by one. As Leon Hunt points out in his essay, “A (Sadistic) Night at the Opera,” the death scenes become the centerpieces of the film. Hunt points out that they are filmed in an entirely different, more artful way than the purely narrative parts of the film. While the narrative sections are filmed in a somewhat traditional fashion, the murder sequences become hyper-stylized visual tour-de-forces that demonstrate not just the levels of brutality that cinema can portray but also the aesthetic heights to which cinema can aspire on a formal level. Blood and Black Lace became a paradigm not just for giallos but for the body count and slasher

at a fashion house, where the models begin being killed off one by one. As Leon Hunt points out in his essay, “A (Sadistic) Night at the Opera,” the death scenes become the centerpieces of the film. Hunt points out that they are filmed in an entirely different, more artful way than the purely narrative parts of the film. While the narrative sections are filmed in a somewhat traditional fashion, the murder sequences become hyper-stylized visual tour-de-forces that demonstrate not just the levels of brutality that cinema can portray but also the aesthetic heights to which cinema can aspire on a formal level. Blood and Black Lace became a paradigm not just for giallos but for the body count and slasher  films that were to come later in the 1970s. Ultimately, however, Bava’s most indisputable contribution to the slasher genre came later with his infamous classic Twitch of the Death Nerve (1971; a.k.a Bay of Blood), a film that will still rival almost any latter-day slasher in terms of its nihilistic depiction of mass murder and butchery. Twitch features extremely graphic murders and sex as well as a plot that completely deconstructs morality and goodness—it is a film about the inherent evil of human nature, and its final moments drive home its image of existence as brutal, unforgiving, and fundamentally evil. It’s a Hobbesian image of existence but without any hope of a leviathan with power enough to enforce order.

films that were to come later in the 1970s. Ultimately, however, Bava’s most indisputable contribution to the slasher genre came later with his infamous classic Twitch of the Death Nerve (1971; a.k.a Bay of Blood), a film that will still rival almost any latter-day slasher in terms of its nihilistic depiction of mass murder and butchery. Twitch features extremely graphic murders and sex as well as a plot that completely deconstructs morality and goodness—it is a film about the inherent evil of human nature, and its final moments drive home its image of existence as brutal, unforgiving, and fundamentally evil. It’s a Hobbesian image of existence but without any hope of a leviathan with power enough to enforce order.

The opening scene of Mario Bava’s The Mask of Satan, which features the legendary Barbara Steele who would go on to star in other Italian productions as well as films by Roger Corman, Federico Fellini, and David Cronenberg.

I

Two back-to-back murders from Bava’s Twitch of the Death Nerve, which feature many of the hallmarks that would later become slasher film cliches: the killer POV shot, axes in the face, and impalement while copulating. Features Graphic violence, sex, blah, blah, blah.

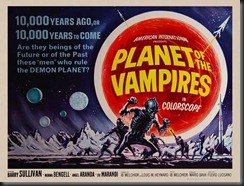

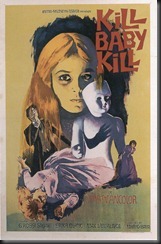

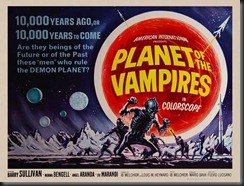

Bava’s influence extends beyond the gothic and giallo genres, but the importance of all his films cannot be conveyed in such a short space. However, four other films bear mentioning: his sci-fi horror film Planet of the Vampires, his arthouse horror films Kill Baby Kill and Lisa and the Devil, and his brutal exploitation film Rabid Dogs. Planet of the Vampires looks like traditional 50s/60s sci-fi fare,

Bava’s influence extends beyond the gothic and giallo genres, but the importance of all his films cannot be conveyed in such a short space. However, four other films bear mentioning: his sci-fi horror film Planet of the Vampires, his arthouse horror films Kill Baby Kill and Lisa and the Devil, and his brutal exploitation film Rabid Dogs. Planet of the Vampires looks like traditional 50s/60s sci-fi fare, but it does actually manage to exude creepiness at various points in the film, and it became the possible inspiration for Ridley Scott’s Alien: the film concerns a ship who lands on a desolate planet after receiving a distress call. There they discover the ruins of a crashed ship and become possessed by some sort of alien life force on the planet. More substantially, Bava also began to craft stylish supernatural films that blend artistry and horror together in a manner similar to the Nicolas Roeg and Dario Argento films we are watching this week. Doubtless, two of his masterpieces remain the

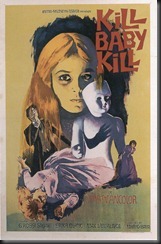

but it does actually manage to exude creepiness at various points in the film, and it became the possible inspiration for Ridley Scott’s Alien: the film concerns a ship who lands on a desolate planet after receiving a distress call. There they discover the ruins of a crashed ship and become possessed by some sort of alien life force on the planet. More substantially, Bava also began to craft stylish supernatural films that blend artistry and horror together in a manner similar to the Nicolas Roeg and Dario Argento films we are watching this week. Doubtless, two of his masterpieces remain the  surrealistic, artful, supernatural thrillers: Kill Baby Kill (1966) and Lisa and the Devil (1972). Kill, Baby, Kill continues in the vein of Bava’s early Gothic films like Mask of Satan, but it also begins to blend in surrealist elements that make it one of Bava’s creepiest films. Set in the Carpathian Mountains (yes, the homeland of a certain Count Dracula), Kill Baby Kill concerns a series of bizarre murders in which the victims are found with coins embedded in their hearts. The film develops into a mystery of witches, evil little girls, and gothic mayhem. But it is really Bava’s ability to craft atmosphere, utilize creepy imagery, and incorporate surrealist elements into it that marks Kill, Baby, Kill as a truly exceptional example of gothic cinema. One of Bava’s

surrealistic, artful, supernatural thrillers: Kill Baby Kill (1966) and Lisa and the Devil (1972). Kill, Baby, Kill continues in the vein of Bava’s early Gothic films like Mask of Satan, but it also begins to blend in surrealist elements that make it one of Bava’s creepiest films. Set in the Carpathian Mountains (yes, the homeland of a certain Count Dracula), Kill Baby Kill concerns a series of bizarre murders in which the victims are found with coins embedded in their hearts. The film develops into a mystery of witches, evil little girls, and gothic mayhem. But it is really Bava’s ability to craft atmosphere, utilize creepy imagery, and incorporate surrealist elements into it that marks Kill, Baby, Kill as a truly exceptional example of gothic cinema. One of Bava’s  final films, Lisa and the Devil still incorporated gothic elements but also began to play surrealistic mindgames with its audience in a manner that in many ways presages David Lynch’s cinema. Featuring the stunning Elke Sommer and Telly (Kojak) Savalas as a demonic character who is potentially the actual devil, Lisa and the Devil feels like a fusion of Bunuel with gothic cinema. A beautiful an artful film, Bava did not live to see Lisa and the Devil released as he filmed it; instead, it was recut as The

final films, Lisa and the Devil still incorporated gothic elements but also began to play surrealistic mindgames with its audience in a manner that in many ways presages David Lynch’s cinema. Featuring the stunning Elke Sommer and Telly (Kojak) Savalas as a demonic character who is potentially the actual devil, Lisa and the Devil feels like a fusion of Bunuel with gothic cinema. A beautiful an artful film, Bava did not live to see Lisa and the Devil released as he filmed it; instead, it was recut as The  House of Exorcism, which used newly shot (non-Bava) footage and a complete re-edit of Bava’s footage to create a rip-off of William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973). Watching both versions of the film provides a useful education about the pivotal role that editing plays in production of the films we see. Finally, one of Bava’s late films also intervened in the exploitation/home-invasion/rape-revenge genre of films: Rabid Dogs (1974; a.k.a. Kidnapped) is a tale of kidnap, torture, and debasement in the vein of Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left (1972), Bo Arne Vibenius’s Thriller: A Cruel Picture (1974), Meir Zarchi’s I Spit on your

House of Exorcism, which used newly shot (non-Bava) footage and a complete re-edit of Bava’s footage to create a rip-off of William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973). Watching both versions of the film provides a useful education about the pivotal role that editing plays in production of the films we see. Finally, one of Bava’s late films also intervened in the exploitation/home-invasion/rape-revenge genre of films: Rabid Dogs (1974; a.k.a. Kidnapped) is a tale of kidnap, torture, and debasement in the vein of Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left (1972), Bo Arne Vibenius’s Thriller: A Cruel Picture (1974), Meir Zarchi’s I Spit on your Grave (1978), and (in the Italian film industry) Ruggero Deodato’s The House on the Edge of the Park (1980). Brutal and nihilistic, Bava’s Rabid Dogs ranks alongside Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971), Wes Craven’s Last House, and Michael Haneke’s Funny Games (1997) as one of the great classics of home invasion/kidnapping films that blend a gritty yet artful aesthetic together with visceral and tense tales of debasement, murder, rape, and human suffering.

Grave (1978), and (in the Italian film industry) Ruggero Deodato’s The House on the Edge of the Park (1980). Brutal and nihilistic, Bava’s Rabid Dogs ranks alongside Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971), Wes Craven’s Last House, and Michael Haneke’s Funny Games (1997) as one of the great classics of home invasion/kidnapping films that blend a gritty yet artful aesthetic together with visceral and tense tales of debasement, murder, rape, and human suffering.

Original Trailer for Mario Bava’s Kill, Baby, Kill.

Original trailer for The House of Exorcism cut of Mario Bava’s Lisa and the Devil.

The late 1960s also saw the rise of Dario Argento, who had worked with spaghetti western maestro Sergio Leone and who had been influenced by the giallo genre and the films of Alfred Hitchcock. In many ways, Argento represents the director who perfects the giallo and presaged the slasher genre that would arise in a few years with the release of Bob Clarke’s Black Christmas (1974) and John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978). Argento kicked off his career with his “Animal Trilogy,” a trilogy of giallos that all featured an animal in the title: The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970), Four Flies on Grey Velvet (1971), and The Cat O’ Nine Tails

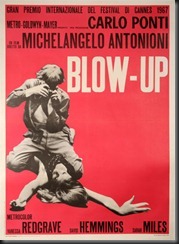

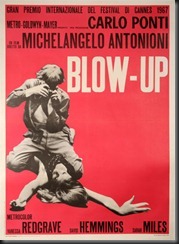

The late 1960s also saw the rise of Dario Argento, who had worked with spaghetti western maestro Sergio Leone and who had been influenced by the giallo genre and the films of Alfred Hitchcock. In many ways, Argento represents the director who perfects the giallo and presaged the slasher genre that would arise in a few years with the release of Bob Clarke’s Black Christmas (1974) and John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978). Argento kicked off his career with his “Animal Trilogy,” a trilogy of giallos that all featured an animal in the title: The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970), Four Flies on Grey Velvet (1971), and The Cat O’ Nine Tails (1971). Obviously influenced by Hitchcock and early Roman Polanski films such as Repulsion (1965), Argento’s first trilogy is a stylish, brutal series of giallos that generally focus upon trying to remember events properly or decipher images or clues in order to reveal the killer. As Hunt’s essay points out, this is a plot element that Argento obviously learned from Italian filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966). Blow-Up concerns a photographer who believes that he snapped photographs of a murder and keeps blowing up his pictures in

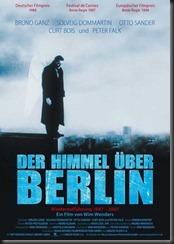

(1971). Obviously influenced by Hitchcock and early Roman Polanski films such as Repulsion (1965), Argento’s first trilogy is a stylish, brutal series of giallos that generally focus upon trying to remember events properly or decipher images or clues in order to reveal the killer. As Hunt’s essay points out, this is a plot element that Argento obviously learned from Italian filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966). Blow-Up concerns a photographer who believes that he snapped photographs of a murder and keeps blowing up his pictures in  order to discover the truth. Argento’s first giallos feature similar plot devices, but they also parallel Antonioni in their love of postmodern architecture. Argento always dwells upon settings and chooses buildings with postmodern designs in order to depict the synthetic space in which people now live, a space completely divorced from the natural. Wim Wenders also employs a similar choice of setting in his classic Wings of Desire (1987), which unfortunately became the inspiration for the crappy Nicolas Cage/Meg Ryan romance called City of Angels (1998). Argento’s first three films might be deemed derivative because of their Hitchcockian aesthetic, but they are remarkably entertaining and stylish films nonetheless that rank alongside the best murder-mystery/psychological thrillers of masters like Alfred Hitchcock, Roman Polanski, and Brian DePalma and that laid the groundwork for Argento’s later masterworks.

order to discover the truth. Argento’s first giallos feature similar plot devices, but they also parallel Antonioni in their love of postmodern architecture. Argento always dwells upon settings and chooses buildings with postmodern designs in order to depict the synthetic space in which people now live, a space completely divorced from the natural. Wim Wenders also employs a similar choice of setting in his classic Wings of Desire (1987), which unfortunately became the inspiration for the crappy Nicolas Cage/Meg Ryan romance called City of Angels (1998). Argento’s first three films might be deemed derivative because of their Hitchcockian aesthetic, but they are remarkably entertaining and stylish films nonetheless that rank alongside the best murder-mystery/psychological thrillers of masters like Alfred Hitchcock, Roman Polanski, and Brian DePalma and that laid the groundwork for Argento’s later masterworks.

Suspiria, which we watched for class, represents Argento’s departure from the pure giallo genre and the first installment of his“Three Mothers Trilogy.” In many ways, Suspiria still feels like a giallo, but it blends in elements of the gothic and supernatural to create a film that is unlike any other and is pure Argento. “The Three Witches Trilogy” concerns three witches named Mater Suspiriorum (The Mother of Sighs), Mater Tenebrarum (The Mother of Darkness), and Mater Lachrymarum (The Mother of Tears) who had three house built for themselves around the turn of the century in

Suspiria, which we watched for class, represents Argento’s departure from the pure giallo genre and the first installment of his“Three Mothers Trilogy.” In many ways, Suspiria still feels like a giallo, but it blends in elements of the gothic and supernatural to create a film that is unlike any other and is pure Argento. “The Three Witches Trilogy” concerns three witches named Mater Suspiriorum (The Mother of Sighs), Mater Tenebrarum (The Mother of Darkness), and Mater Lachrymarum (The Mother of Tears) who had three house built for themselves around the turn of the century in  three different cities: New York, Rome, and Freiburg. Suspiria concerns Mater Suspiriorum in Freiburg whose house doubles as a ballet academy. With Suspiria, Argento began to develop a truly distinctive style that played with vibrant colors, bizarre shot positions, and elaborate camera movements to accentuate his weird and horrific story lines. Argento continued the “Three Mothers Trilogy” with Inferno (1980), which concerned Mater Tenebrarum in

three different cities: New York, Rome, and Freiburg. Suspiria concerns Mater Suspiriorum in Freiburg whose house doubles as a ballet academy. With Suspiria, Argento began to develop a truly distinctive style that played with vibrant colors, bizarre shot positions, and elaborate camera movements to accentuate his weird and horrific story lines. Argento continued the “Three Mothers Trilogy” with Inferno (1980), which concerned Mater Tenebrarum in  New York. Then, Argento went almost thirty years before completing the trilogy with its final film The Mother of Tears (2007), which depicts Mater Lachrymarum’s return to power in Rome. Argento then went on to direct some of the most classic examples of the giallo genre: Deep Red (1975) and Tenebrae (1980), both of which blended Argento’s Hitchcockian murder-mysteries together with his ultra-brutal and often surrealistic aesthetic. Argento’s “bad objects,” his blends of artistic and horrific filmmaking, have left an indelible mark upon the face of horror cinema, which is why he remains of the true masters of the genre.

New York. Then, Argento went almost thirty years before completing the trilogy with its final film The Mother of Tears (2007), which depicts Mater Lachrymarum’s return to power in Rome. Argento then went on to direct some of the most classic examples of the giallo genre: Deep Red (1975) and Tenebrae (1980), both of which blended Argento’s Hitchcockian murder-mysteries together with his ultra-brutal and often surrealistic aesthetic. Argento’s “bad objects,” his blends of artistic and horrific filmmaking, have left an indelible mark upon the face of horror cinema, which is why he remains of the true masters of the genre.

Trailer for Argento’s classic giallo, Deep Red.

I am saving the infamous Italian gore-master Lucio Fulci for next week, but I wanted to briefly discuss probably the most infamous Italian horror director of all time: Ruggero Deodato. The release of George A. Romero’s classic Dawn of the Dead (1978) inspired a slew of copy-cat zombie films in Italian cinema as well as giving birth to what is known as the cannibal genre. While Italian horror films often aped blockbuster American cinema (there are more than one rip-offs of Alien), they at times developed these seemingly derivative films into truly original works. The cannibal genre—a genre almost exclusive to Italian cinema —took the zombie film’s love of cannibalistic scenes, evisceration, dismemberment, etc. and transplanted it into the South American rain forest. Instead of zombies, the films feature living cannibal tribes who have been left behind by civilization. The films regularly feature graphic and horrific violence/torture, rape and sexual violence, and (often real) scenes of

—took the zombie film’s love of cannibalistic scenes, evisceration, dismemberment, etc. and transplanted it into the South American rain forest. Instead of zombies, the films feature living cannibal tribes who have been left behind by civilization. The films regularly feature graphic and horrific violence/torture, rape and sexual violence, and (often real) scenes of  animal mutilation. Deodato directed a trilogy of cannibal films: Jungle Holocaust (1977), Cannibal Holocaust (1980), and Cut and Run (to use their American names; 1985). But he remains most (in)famous for Cannibal Holocaust, the middle and most brutal entry of the trilogy. A film that features ritual rape and abortion, graphic and real animal cruelty, mutilation, cannibalism, impalement, etc., Cannibal Holocaust was so realistic and disturbing at the time of its release that Deodato had to actually produce the actors and actresses in court to prove that it was not a snuff film. For me, it is the scenes of animal cruelty and torture that are truly hard to watch and disgusting

animal mutilation. Deodato directed a trilogy of cannibal films: Jungle Holocaust (1977), Cannibal Holocaust (1980), and Cut and Run (to use their American names; 1985). But he remains most (in)famous for Cannibal Holocaust, the middle and most brutal entry of the trilogy. A film that features ritual rape and abortion, graphic and real animal cruelty, mutilation, cannibalism, impalement, etc., Cannibal Holocaust was so realistic and disturbing at the time of its release that Deodato had to actually produce the actors and actresses in court to prove that it was not a snuff film. For me, it is the scenes of animal cruelty and torture that are truly hard to watch and disgusting because they are not staged—they are real. Certain versions of the film cut these scenes out to make it more amenable to modern-day audiences. But Cannibal Holocaust proved significant for reasons beyond its shocking images—it was also the first film to feature the found footage technique that has become a mainstay of the horror film industry with works like The Blair Witch Project (1999), Cloverfield (2008), [Rec] (2007; and its American remake Quarantine [2008]), Paranormal Activity (2007), The Last Exorcism (2010), and the upcoming Apollo 18 (2011). Cannibal Holocaust concerns a group of

because they are not staged—they are real. Certain versions of the film cut these scenes out to make it more amenable to modern-day audiences. But Cannibal Holocaust proved significant for reasons beyond its shocking images—it was also the first film to feature the found footage technique that has become a mainstay of the horror film industry with works like The Blair Witch Project (1999), Cloverfield (2008), [Rec] (2007; and its American remake Quarantine [2008]), Paranormal Activity (2007), The Last Exorcism (2010), and the upcoming Apollo 18 (2011). Cannibal Holocaust concerns a group of  researchers who plunge deep into the South American rain forest to find out what happened to a group of documentary filmmakers who disappeared in the region. Among one of the cannibal tribes, they discover the documentarians’ film canisters, which they take with them back to the United States. When they watch the films, they discover horrors beyond their expectations. The initial villains of these uncut films are the filmmakers who rape and brutalize the native people, torture animals, and set villages on fire. Ultimately, of course, the filmmakers meet a

researchers who plunge deep into the South American rain forest to find out what happened to a group of documentary filmmakers who disappeared in the region. Among one of the cannibal tribes, they discover the documentarians’ film canisters, which they take with them back to the United States. When they watch the films, they discover horrors beyond their expectations. The initial villains of these uncut films are the filmmakers who rape and brutalize the native people, torture animals, and set villages on fire. Ultimately, of course, the filmmakers meet a gruesome end which is captured from a first person vantage point on the films. In the final analysis, Cannibal Holocaust is actually a rather profound film about how our ideas of savagery and civilization are flawed and about how humanity remains brutal and violent at its core. An unnerving film htat should not be watched by most people, Cannibal Holocaust remains one of the great testaments to how horror can use its brutal imagery to evoke a particular message.

gruesome end which is captured from a first person vantage point on the films. In the final analysis, Cannibal Holocaust is actually a rather profound film about how our ideas of savagery and civilization are flawed and about how humanity remains brutal and violent at its core. An unnerving film htat should not be watched by most people, Cannibal Holocaust remains one of the great testaments to how horror can use its brutal imagery to evoke a particular message.

The theatrical trailer for one of the most infamous films of all time. The trailer is fairly tame and features none of the graphic violence of the film, although it does feature shots suggestive of the violence that will ensue during those parts of the film. The trailer does contain full-frontal nudity, an occurrence that was common for Grindhouse trailers of the 70s and 80s that were never meant to be seen by mainstream audiences. And, NO, the people in the trailer were not actually eaten despite its claims.

Also, for a bit of a change, old Al will offer you his horror film pick of the week. This week’s choice is Insidious, the new supernatural/haunted house film from director James Wan (Saw [2004]) and producer Jason Blum (Paranormal Activity). Insidious is, quite frankly, scary as hell. If you’re like me, which you most likely are not, you crave that feeling from a horror film that you had as a child, a feeling of dread that persists long after the film is over and makes you afraid to look in mirrors, turn off the lights, or go to sleep. It’s a film that makes you want to watch cartoons for the rest of the evening in a vain attempt to expunge its imagery from

Also, for a bit of a change, old Al will offer you his horror film pick of the week. This week’s choice is Insidious, the new supernatural/haunted house film from director James Wan (Saw [2004]) and producer Jason Blum (Paranormal Activity). Insidious is, quite frankly, scary as hell. If you’re like me, which you most likely are not, you crave that feeling from a horror film that you had as a child, a feeling of dread that persists long after the film is over and makes you afraid to look in mirrors, turn off the lights, or go to sleep. It’s a film that makes you want to watch cartoons for the rest of the evening in a vain attempt to expunge its imagery from your mind. Yes, that’s what I crave from a horror film, and it’s a feeling I rarely get anymore, but Insidious not only made me jump and even scream at one point while watching it but left me feeling uneasy for the rest of the evening. What makes it different from less successful haunted house films? Quite simply, its imagery. Its demonic imagery is original, visually striking, and truly creepy. The film also proves so successful because it foregoes most of the tired horror film cliches, particularly in terms of music. The film does not always let you know when to be scared with musical cues like most horror cinema. Instead, its imagery shocks you because you or not expecting it or it is located in areas where you don’t at first notice it. It is a film of half-seen things that make you think you saw something before confirming it with a second glance. Insidious participates in the tradition of classic haunted house films like Robert Wise’s The Haunting (1963), The Amityville Horror (1979), Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), and Tobe Hooper’s Poltergeist. (1982), but it also knows how to deviate from the tradtion, strike out new space, and create unforgettable horror images.

your mind. Yes, that’s what I crave from a horror film, and it’s a feeling I rarely get anymore, but Insidious not only made me jump and even scream at one point while watching it but left me feeling uneasy for the rest of the evening. What makes it different from less successful haunted house films? Quite simply, its imagery. Its demonic imagery is original, visually striking, and truly creepy. The film also proves so successful because it foregoes most of the tired horror film cliches, particularly in terms of music. The film does not always let you know when to be scared with musical cues like most horror cinema. Instead, its imagery shocks you because you or not expecting it or it is located in areas where you don’t at first notice it. It is a film of half-seen things that make you think you saw something before confirming it with a second glance. Insidious participates in the tradition of classic haunted house films like Robert Wise’s The Haunting (1963), The Amityville Horror (1979), Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), and Tobe Hooper’s Poltergeist. (1982), but it also knows how to deviate from the tradtion, strike out new space, and create unforgettable horror images.

No comments:

Post a Comment