In their classic critique of Marxism and psychoanalysis, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1972), French philosopher Gilles Deleuze and French psychoanalyst Felix Guattari claim that zombie has become the sole remaining myth of our culture: “The only modern myth is the myth of zombies—mortified schizos, good for work, brought back to reason. In this sense the primitive and the barbarian, with their ways of coding death, are children in comparison to modern man and

In their classic critique of Marxism and psychoanalysis, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1972), French philosopher Gilles Deleuze and French psychoanalyst Felix Guattari claim that zombie has become the sole remaining myth of our culture: “The only modern myth is the myth of zombies—mortified schizos, good for work, brought back to reason. In this sense the primitive and the barbarian, with their ways of coding death, are children in comparison to modern man and his axiomatic (so many unemployed are needed, so many deaths, the Algerian War doestn’t kill more people than weekend automobile accidents, planned death in Bengal etc.)” (335). While one could maintain that the popularity of vampires marks them as a popular modern myth as well, they seem to enact a kind of gothic-erotic wish fulfillment instead of functioning as a genuine myth Unlike the romantic nostalgia associated with vampires, zombies represent the modern

his axiomatic (so many unemployed are needed, so many deaths, the Algerian War doestn’t kill more people than weekend automobile accidents, planned death in Bengal etc.)” (335). While one could maintain that the popularity of vampires marks them as a popular modern myth as well, they seem to enact a kind of gothic-erotic wish fulfillment instead of functioning as a genuine myth Unlike the romantic nostalgia associated with vampires, zombies represent the modern  and (perhaps even more so) postmodern human condition. Zombie films have always used the undead as metaphors for slavery, the oppression of minorities, mindless consumerism, militarism, or even just drunk British people (Shaun of the Dead [2004]). But Deleuze and Guattari are making a much more profound point about the figure of the zombie—the zombie is not just an empty signifier that can be plugged into specific contexts in order

and (perhaps even more so) postmodern human condition. Zombie films have always used the undead as metaphors for slavery, the oppression of minorities, mindless consumerism, militarism, or even just drunk British people (Shaun of the Dead [2004]). But Deleuze and Guattari are making a much more profound point about the figure of the zombie—the zombie is not just an empty signifier that can be plugged into specific contexts in order to offer social criticism on some particular current event. No, the zombie is a signifier that points directly at us the audience—We Are The Real Zombies! If zombie has a signified, it is us, the audience members—of course, if we follow Lacan, then the signified does not exist because signifiers only have meaning in relation to other signifiers. If the zombie is an empty

to offer social criticism on some particular current event. No, the zombie is a signifier that points directly at us the audience—We Are The Real Zombies! If zombie has a signified, it is us, the audience members—of course, if we follow Lacan, then the signified does not exist because signifiers only have meaning in relation to other signifiers. If the zombie is an empty  signifier, then it is because it points to the emptiness inside everyone of us. In many ways, the zombie resonates so profoundly not just because it can be used to symbolize certain groups of people but because it represents how all of us have become oppressed by the institutions and the machinery of power and control as well as our consumerist culture of luxury and entertainment. Power and the media strive to make us mindless automatons—that is the true message of the zombie film.

signifier, then it is because it points to the emptiness inside everyone of us. In many ways, the zombie resonates so profoundly not just because it can be used to symbolize certain groups of people but because it represents how all of us have become oppressed by the institutions and the machinery of power and control as well as our consumerist culture of luxury and entertainment. Power and the media strive to make us mindless automatons—that is the true message of the zombie film.

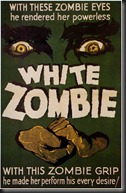

The myth of the zombie derives from West African Vondon and its descendent Haitian voodou both of which have rituals that could supposedly reanimate corpses to become undead slaves. The earliest zombie films deal precisely with this version of the zombie. Early examples of zombie films include White Zombie (1932) starring Bela (Dracula) Lugosi, producer Val Lewton and director Jacques Tourneur’s I Walked with a Zombie (1943), and Hammer Studio’s The Plague of Zombies (1966). These films all dealt with evil occultists who use particular rituals to reanimate corpses and use them as slave labor. These films bear little resemblance to the gory zombie films that would begin to define the genre from the late 60s onward. These early films

The myth of the zombie derives from West African Vondon and its descendent Haitian voodou both of which have rituals that could supposedly reanimate corpses to become undead slaves. The earliest zombie films deal precisely with this version of the zombie. Early examples of zombie films include White Zombie (1932) starring Bela (Dracula) Lugosi, producer Val Lewton and director Jacques Tourneur’s I Walked with a Zombie (1943), and Hammer Studio’s The Plague of Zombies (1966). These films all dealt with evil occultists who use particular rituals to reanimate corpses and use them as slave labor. These films bear little resemblance to the gory zombie films that would begin to define the genre from the late 60s onward. These early films play more into the gothic-styles of horror filmmaking popularized by Universal Studios in the 1930s and Hammer Studios in the 50s and 60s. But the 1960s fundamentally changed the face of horror cinema as they altered the landscape of cinema more generally—see the French new wave directors (Goddard, Malle, Resnais, Truffaut, Varda); the post-neorealism Italian filmmakers like Federico Fellini, Michelangelo Antonioni, and Pierre Paolo Pasolini; and the rise of Stanley Kubrick for just a few examples of how cinema was changing. Of course, as cheesy as it might sound, the 1960s changed history in profound ways. However, in the realm of horror cinema, these changes were not in keeping with the peace-loving mentality of the hippies. No, they were changes that lead down a path filled with sexual perversions and blood-soaked nightmares.

play more into the gothic-styles of horror filmmaking popularized by Universal Studios in the 1930s and Hammer Studios in the 50s and 60s. But the 1960s fundamentally changed the face of horror cinema as they altered the landscape of cinema more generally—see the French new wave directors (Goddard, Malle, Resnais, Truffaut, Varda); the post-neorealism Italian filmmakers like Federico Fellini, Michelangelo Antonioni, and Pierre Paolo Pasolini; and the rise of Stanley Kubrick for just a few examples of how cinema was changing. Of course, as cheesy as it might sound, the 1960s changed history in profound ways. However, in the realm of horror cinema, these changes were not in keeping with the peace-loving mentality of the hippies. No, they were changes that lead down a path filled with sexual perversions and blood-soaked nightmares.

Trailer for White Zombie starring the iconic Bela Lugosi, who played Dracula in the original 1931 Universal Studios version of the film.

Trailer for famous horror producer Val Lewton and director Jacques Tourneur’s I Walked with a Zombie.

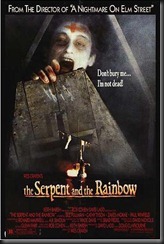

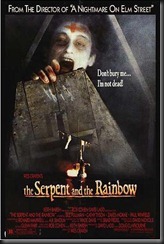

While the Haitian voodoo trend of Zombie films died out for the most part, it continued to linger in certain examples of the genre. In particular, one more contemporary film chillingly explores the voodoo myth of the zombie: Wes Craven’s The Serpent and the Rainbow (1988). From director Wes Craven (The Last House on the Left [1972], The Hills Have Eyes [1977], A Nightmare on Elm St. [1984], and Scream [1996]), The Serpent and the Rainbow is a loose adaptation of Wade Davis’s non-fiction study of the same name. Davis’s book recounts his investigations into a man who was supposedly buried and returned to life. Craven’s film takes this basic premise and turns into a horrific thriller filled with bizarre neurotoxins, live burial, covert government torture, and revolution. A genuinely creepy and stylish exploration of the lines between fact and fiction and life and death, The Serpent and the Rainbow remains a standout in the history of zombie films because of its originality and its attempt to grapple with the original myths that gave birth to film genre.

man who was supposedly buried and returned to life. Craven’s film takes this basic premise and turns into a horrific thriller filled with bizarre neurotoxins, live burial, covert government torture, and revolution. A genuinely creepy and stylish exploration of the lines between fact and fiction and life and death, The Serpent and the Rainbow remains a standout in the history of zombie films because of its originality and its attempt to grapple with the original myths that gave birth to film genre.

Trailer for Wes Craven’s The Serpent and the Rainbow.

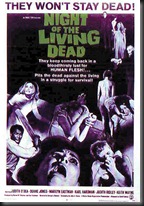

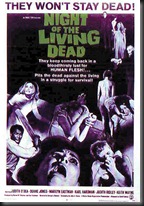

The face of zombie cinema changed forever with the release of George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968), which introduced all the basic elements of what most consider to be a zombie film: swarms of slow-walking zombies in various states of decay, zombie feasting scenes, the need to kill them with blunt trauma to the head. Romero’s taunt thriller about a group of people trapped in a rural house surrounded by zombies did not become a classic immediately—it developed a cult following steadily over the years. Still, it marked a sea change in horror cinema that took place over the course of the 1960s. Four American and

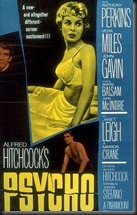

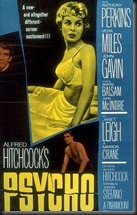

The face of zombie cinema changed forever with the release of George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968), which introduced all the basic elements of what most consider to be a zombie film: swarms of slow-walking zombies in various states of decay, zombie feasting scenes, the need to kill them with blunt trauma to the head. Romero’s taunt thriller about a group of people trapped in a rural house surrounded by zombies did not become a classic immediately—it developed a cult following steadily over the years. Still, it marked a sea change in horror cinema that took place over the course of the 1960s. Four American and  British films, in particular, began to change the face of horror by directing it into more perverse, twisted, and gory avenues. Alongside Romero’s Night, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960), and Herschell Gordon Lewis’s Blood Feast (1963) began leading English-speaking cinema down a dark road of perverts, psychotics, cannibals, and gorefests that paved the way for the even more depraved horror cinema that would arrive in the 1970s and 80s. But it would be Romero’s second entry in his zombie series that would bring zombie cinema onto the world stage.

British films, in particular, began to change the face of horror by directing it into more perverse, twisted, and gory avenues. Alongside Romero’s Night, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960), and Herschell Gordon Lewis’s Blood Feast (1963) began leading English-speaking cinema down a dark road of perverts, psychotics, cannibals, and gorefests that paved the way for the even more depraved horror cinema that would arrive in the 1970s and 80s. But it would be Romero’s second entry in his zombie series that would bring zombie cinema onto the world stage.

In 1978, Romero released his sequel to Night of the Living Dead: Dawn of the Dead, which followed a group of survivors who take shelter in a mall during the zombie apocalypse. Featuring hordes of zombies unseen in cinematic history up until that point and levels of gore that beat anything previously released, Dawn of the Dead was an epic horror experience that redefined the horror genre and the zombie film. Set in a mall when such shopping meccas were first on the rise, Dawn of the Dead remains a powerful critique of consumerism and materialism—it is about the worthless trinkets over which we obsess but that are have no value when it comes to survival. The film was released in an edited form in the United States.

In 1978, Romero released his sequel to Night of the Living Dead: Dawn of the Dead, which followed a group of survivors who take shelter in a mall during the zombie apocalypse. Featuring hordes of zombies unseen in cinematic history up until that point and levels of gore that beat anything previously released, Dawn of the Dead was an epic horror experience that redefined the horror genre and the zombie film. Set in a mall when such shopping meccas were first on the rise, Dawn of the Dead remains a powerful critique of consumerism and materialism—it is about the worthless trinkets over which we obsess but that are have no value when it comes to survival. The film was released in an edited form in the United States. Dario Argento edited the cut of the film for its release in Europe, where it was given the title Zombi. Later, the fully uncut version of the film was released for the U.S. home video marketplace. The film proved profoundly influential upon American and European cinema, particularly the Italian zombie and cannibal films that were soon to follow. Zack Snyder directed a partially successfully but ultimately flawed remake of Dawn of the Dead in 2004—Snyder also directed 300 (2007), Watchmen (2009), and Suckerpunch (2011), which is in theaters right now. Romero followed up Dawn of the Dead with Day of the Dead (1985). Set in an underground military base, Day of the Dead concerns a small group of soldiers and scientists surviving after zombies have taken over the globe. By having the scientists

Dario Argento edited the cut of the film for its release in Europe, where it was given the title Zombi. Later, the fully uncut version of the film was released for the U.S. home video marketplace. The film proved profoundly influential upon American and European cinema, particularly the Italian zombie and cannibal films that were soon to follow. Zack Snyder directed a partially successfully but ultimately flawed remake of Dawn of the Dead in 2004—Snyder also directed 300 (2007), Watchmen (2009), and Suckerpunch (2011), which is in theaters right now. Romero followed up Dawn of the Dead with Day of the Dead (1985). Set in an underground military base, Day of the Dead concerns a small group of soldiers and scientists surviving after zombies have taken over the globe. By having the scientists  experiment on zombies and depicting the tense relations between the scientists and soldiers, Day of the Dead screens like a dark parable about militarism, the misuse of science, and the frictional relationship between technology and the war machine. At all costs, avoid the 2008 remake of Day of the Dead which features the always-less-than-impressive Mena Suvari. After Day of the Dead, Romero pursued other non-zombie related projects for over two decades. Then, he finally released another entry in his zombie series in 2005 entitled Land of the Dead. Unlike its three predecessors, the film featured several well-known actors and actresses. Having already explored race, consumerism, and militarism, Romero trained his sites on class hierarchies for the fourth entry in his series.

experiment on zombies and depicting the tense relations between the scientists and soldiers, Day of the Dead screens like a dark parable about militarism, the misuse of science, and the frictional relationship between technology and the war machine. At all costs, avoid the 2008 remake of Day of the Dead which features the always-less-than-impressive Mena Suvari. After Day of the Dead, Romero pursued other non-zombie related projects for over two decades. Then, he finally released another entry in his zombie series in 2005 entitled Land of the Dead. Unlike its three predecessors, the film featured several well-known actors and actresses. Having already explored race, consumerism, and militarism, Romero trained his sites on class hierarchies for the fourth entry in his series. Featuring John Leguizamo, Dennis Hopper, and Asia Argento (Dario Argento’s daughter), Land of the Dead was the first big-budget entry in the series, and perhaps for that reason it felt flatter and less visceral than its more independent predecessors. The film concerns a lone, elegant skyscraper apartment building that houses the rich. Around the base of this tower, a ghetto has grown up that features the poor, working class people that either work as servants for or provide goods to the rich or eek out an existence as black marketeers, prize fighters, prostitutes, etc. They are all protected by a giant fence that encloses the skyscraper and its environs. Of course, the zombies arrive and breach the perimeter

Featuring John Leguizamo, Dennis Hopper, and Asia Argento (Dario Argento’s daughter), Land of the Dead was the first big-budget entry in the series, and perhaps for that reason it felt flatter and less visceral than its more independent predecessors. The film concerns a lone, elegant skyscraper apartment building that houses the rich. Around the base of this tower, a ghetto has grown up that features the poor, working class people that either work as servants for or provide goods to the rich or eek out an existence as black marketeers, prize fighters, prostitutes, etc. They are all protected by a giant fence that encloses the skyscraper and its environs. Of course, the zombies arrive and breach the perimeter  protecting the enclave of humans, which consequently disrupts the boundaries separating the haves from the have nots. Land of the Dead still demonstrates Romero’s ability to use genre films as a mean of commenting upon socio-political issues, but it just feels less visceral than its predecessors. Thankfully, with the next entry in the series, Romero returned to his indy origins and released his found footage take on the zombie genre: Diary of the Dead (2007). Like The Blair Witch Project (1999) and Cloverfield (2008), Diary of the Dead consists of the first-person perspective of a Pitt film student attempting to document the zombie apocalypse. What unfolds is a taunt, brutal, and often funny exploration of our culture’s obsession with reality television, Youtube videos, and horrific news footage. Unfortunately, Romero followed Diary of the Dead with the first genuine flop of the series: Survival of the Dead (2009). Set on island community during the zombie uprising, Survival seems to want to offer a commentary on civil war and intra-community conflicts, but if fails to be anything but a piece of cheesy, forgettable zombie cinema trash.

protecting the enclave of humans, which consequently disrupts the boundaries separating the haves from the have nots. Land of the Dead still demonstrates Romero’s ability to use genre films as a mean of commenting upon socio-political issues, but it just feels less visceral than its predecessors. Thankfully, with the next entry in the series, Romero returned to his indy origins and released his found footage take on the zombie genre: Diary of the Dead (2007). Like The Blair Witch Project (1999) and Cloverfield (2008), Diary of the Dead consists of the first-person perspective of a Pitt film student attempting to document the zombie apocalypse. What unfolds is a taunt, brutal, and often funny exploration of our culture’s obsession with reality television, Youtube videos, and horrific news footage. Unfortunately, Romero followed Diary of the Dead with the first genuine flop of the series: Survival of the Dead (2009). Set on island community during the zombie uprising, Survival seems to want to offer a commentary on civil war and intra-community conflicts, but if fails to be anything but a piece of cheesy, forgettable zombie cinema trash.

Trailer for George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead.

Opening credits of Zack Snyder’s remake of Dawn of the Dead, one of the best parts of the film, featuring Johnny Cash’s When the Man Comes Around.

A short scene from George A. Romero’s Diary of the Dead, which gives a taste of its found footage style.

But Romero did not have the market cornered on zombie films. Three years after Night of the

Living Dead, Spain saw the emergence of its own zombie film auteur: Amondo de Ossorio. Ossorio’s release of Tombs of the Blind Dead (1971) remains a unique take on the genre with its depiction of undead, blind Knights Templar who return from the grave to seek new victims. Practitioners of Satanic rites while they lived, this particular group of Templars sought the secret of  eternal life, but they were eventually executed and crows plucked out their eyes. A creepy and stylish supernatural film, Tombs of the Blind Dead is not exactly a zombie film in the Romero sense—the Templars are not rotten-looking corpses but instead bear a stronger

eternal life, but they were eventually executed and crows plucked out their eyes. A creepy and stylish supernatural film, Tombs of the Blind Dead is not exactly a zombie film in the Romero sense—the Templars are not rotten-looking corpses but instead bear a stronger  resemblance to mummies. Additionally, they are not mindless like Romero’s zombies but instead retain their deadly purpose even in their reanimated forms. However, they do return from the grave to feast on the flesh of the living, so the film is still pure zombie at its core. The film became a cult hit and lead to three sequels that further developed the tale of the undead Templars: Return of the Blind Dead (1973), The Ghost Galleon (1974), and Night of the Seagulls (1975). All four films have gone on to become highly influential horror classics whether one considers them to be zombie films or not—Ossorio himself holds that they are not zombie films. The

resemblance to mummies. Additionally, they are not mindless like Romero’s zombies but instead retain their deadly purpose even in their reanimated forms. However, they do return from the grave to feast on the flesh of the living, so the film is still pure zombie at its core. The film became a cult hit and lead to three sequels that further developed the tale of the undead Templars: Return of the Blind Dead (1973), The Ghost Galleon (1974), and Night of the Seagulls (1975). All four films have gone on to become highly influential horror classics whether one considers them to be zombie films or not—Ossorio himself holds that they are not zombie films. The early 1970s also saw the release of Spanish director Jorge Grau’s stylish, beautifully filmed and twisted zombie classic: Let Sleeping Corpses Lie (a.k.a. The Living Dead at the Manchester Morgue; 1974). Shot on location in the English countryside, Let Sleeping Corpses Lie followed in the Romero zombie tradition. The film concerns an experimental machine that uses ultra-sonic waves to cause bugs to kill one another off, thus protecting crops from damage. But, of course, the machine begins to cause the dead to return from the grave.

early 1970s also saw the release of Spanish director Jorge Grau’s stylish, beautifully filmed and twisted zombie classic: Let Sleeping Corpses Lie (a.k.a. The Living Dead at the Manchester Morgue; 1974). Shot on location in the English countryside, Let Sleeping Corpses Lie followed in the Romero zombie tradition. The film concerns an experimental machine that uses ultra-sonic waves to cause bugs to kill one another off, thus protecting crops from damage. But, of course, the machine begins to cause the dead to return from the grave. The creepy awakening of the Blind Dead from their Hellish slumber.

An amusing, short trailer for Let Sleeping Corpses Lie. In this trailer the film is called Don’t Open the Window—the film was released under a slew of different titles. There was a major trend in the 70s of beginning horror film titles with the word “Don’t”: Don’t Look in the Basement, Don’t Open the Door, Don’t Go Near the Park, etc. This trend was parodied by Edgar (Shaun of the Dead, Hot Fuzz, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World) Wright’s fake trailer entitled simply “Don’t”, which appeared in Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez’s Grindhouse.

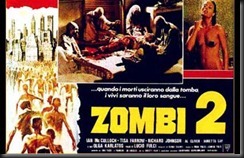

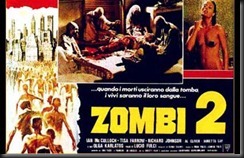

The release of Romero’s Dawn of the Dead in Europe, where it was called simply Zombi, sparked a firestorm of copycat zombie films. Most notably, Italian genre director Lucio Fulci (the so-called “Godfather of Gore”) released his own trilogy of zombie films in the early 1980s, which have gone own to develop a cult following that ranks second only to Romero’s original trilogy of zombie films. Along with Mario Bava, Dario Argento, Michele Soavi, Umberto Lenzi, and Pupi Avati, Fulci remains ones one of the gods of Italian horror cinema.

The release of Romero’s Dawn of the Dead in Europe, where it was called simply Zombi, sparked a firestorm of copycat zombie films. Most notably, Italian genre director Lucio Fulci (the so-called “Godfather of Gore”) released his own trilogy of zombie films in the early 1980s, which have gone own to develop a cult following that ranks second only to Romero’s original trilogy of zombie films. Along with Mario Bava, Dario Argento, Michele Soavi, Umberto Lenzi, and Pupi Avati, Fulci remains ones one of the gods of Italian horror cinema. A prolific director, who—like Bava—directed in other genres like westerns, Fulci remains famous for his stylish brutality and his plots that are sometimes difficult to follow due to bad writing and editing. But these flaws actually add a surrealistic element to his films that works well with his best films—his films range from the truly sublime to the utterly

A prolific director, who—like Bava—directed in other genres like westerns, Fulci remains famous for his stylish brutality and his plots that are sometimes difficult to follow due to bad writing and editing. But these flaws actually add a surrealistic element to his films that works well with his best films—his films range from the truly sublime to the utterly  unwatchable. Fulci staked his claim in the zombie film genre with the unforgettable Zombi 2 (or sometimes just Zombie;1979). Released only a year after Romero’s Dawn of the Dead, Fulci’s film studio attempted to cash in on the success of Zombi (as it was released in Italy) by claiming that Fulci’s film was a sequel—this is very common practice in Italian genre cinema. Fulci’s film has no relation to Romero’s classic, yet it mangaged to become a zombie classic in its own right. Featuring stylish depictions of brutal, over-the-top scenes, Zombi 2 features numerous unforgettable moments: zombie versus shark, the POV shot of zombies rising from the tomb, a scene of graphic ocular damage, etc. One year later, Fulci released a follow-up entitled The Gates

unwatchable. Fulci staked his claim in the zombie film genre with the unforgettable Zombi 2 (or sometimes just Zombie;1979). Released only a year after Romero’s Dawn of the Dead, Fulci’s film studio attempted to cash in on the success of Zombi (as it was released in Italy) by claiming that Fulci’s film was a sequel—this is very common practice in Italian genre cinema. Fulci’s film has no relation to Romero’s classic, yet it mangaged to become a zombie classic in its own right. Featuring stylish depictions of brutal, over-the-top scenes, Zombi 2 features numerous unforgettable moments: zombie versus shark, the POV shot of zombies rising from the tomb, a scene of graphic ocular damage, etc. One year later, Fulci released a follow-up entitled The Gates  of Hell (1980; a.k.a. City of the Living Dead). The film has no connection to Zombi 2 other than its featuring zombies, but it continued to showcase Fulci’s distinctive style. Featuring undead priests, tablesaw deaths, vomiting guts, maggot showers, blow-up dolls, and an ending that still remains inexplicable, The

of Hell (1980; a.k.a. City of the Living Dead). The film has no connection to Zombi 2 other than its featuring zombies, but it continued to showcase Fulci’s distinctive style. Featuring undead priests, tablesaw deaths, vomiting guts, maggot showers, blow-up dolls, and an ending that still remains inexplicable, The  Gates of Hell remains a bizarro zombie classic that unfolds predominately in close-ups. The film almost feels like Bergman in its adoration of the human face, but it is like watching Bergman after he has watched nothing but pornography, horror, and exploitation films for a year straight. Finally, Fulci rounded out his zombie trilogy with The Beyond (1981), a stylish tale of the undead set in New Orleans. Fulci mades dozens of films before and after his zombie trilogy, but they still remain some of his most iconic works.

Gates of Hell remains a bizarro zombie classic that unfolds predominately in close-ups. The film almost feels like Bergman in its adoration of the human face, but it is like watching Bergman after he has watched nothing but pornography, horror, and exploitation films for a year straight. Finally, Fulci rounded out his zombie trilogy with The Beyond (1981), a stylish tale of the undead set in New Orleans. Fulci mades dozens of films before and after his zombie trilogy, but they still remain some of his most iconic works.

A clip showing some of the highlights of Lucio Fulci’s Zombi 2.

The amazingly bizarre and creepy first ten minutes of Fulci’s The Gates of Hell.

The 1980s saw the continuation of Romero and Fulci’s zombie series along with the release of numerous other zombie films, but the decade also witnessed the beginning of a new take on the genre—the zombie comedy. Undoubtedly, the first example of a zombie film that strives for both comedy and horror is Sam Raimi’s cult classic The Evil Dead (1981). While the film may not technically be a zombie film because the reanimated bodies are actually possessed by demons, it still feels like a zombie film in its depiction of corpses that come back from the grave to torment the

The 1980s saw the continuation of Romero and Fulci’s zombie series along with the release of numerous other zombie films, but the decade also witnessed the beginning of a new take on the genre—the zombie comedy. Undoubtedly, the first example of a zombie film that strives for both comedy and horror is Sam Raimi’s cult classic The Evil Dead (1981). While the film may not technically be a zombie film because the reanimated bodies are actually possessed by demons, it still feels like a zombie film in its depiction of corpses that come back from the grave to torment the living. Raimi’s first Evil Dead film still remains his masterpiece in my mind because it seamlessly blends creepiness together with humor without becoming slapsticky like his later entries in the series. The Evil Dead concerns a group of friends who go to a cabin for a weekend vacation only to discover that it was previously inhabited by an anthropologist who specialized in the occult. The male characters end up discovering the Necronomicon—a plot device that Raimi borrows from H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos—a book bound in flesh and written in blood that offers instructions on summoning demons and reviving the dead. Of course, the

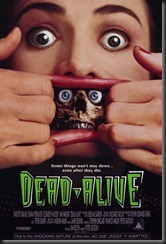

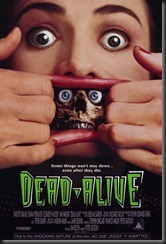

living. Raimi’s first Evil Dead film still remains his masterpiece in my mind because it seamlessly blends creepiness together with humor without becoming slapsticky like his later entries in the series. The Evil Dead concerns a group of friends who go to a cabin for a weekend vacation only to discover that it was previously inhabited by an anthropologist who specialized in the occult. The male characters end up discovering the Necronomicon—a plot device that Raimi borrows from H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos—a book bound in flesh and written in blood that offers instructions on summoning demons and reviving the dead. Of course, the  men read from the book and unleash an unspeakable evil upon themselves. The film that started Bruce Campbell’s career as a butch horror movie ass-kicker, The Evil Dead remains a stylish, creepy, and hilarious take on the zombie genre. Raimi followed it up with two equally classic sequels: The Evil Dead 2 (1987) and Army of Darkness (1992). The films get increasingly silly and slapsticky as they go along and hence—in my humble opinion—lose the subtle, black humor of the original. The 1980s and early 90s also the release of other classic zombie comedies such as The Return of the Living Dead (1985), which spawned its own massive series of films, and Peter Jackson’s Dead Alive (1992), which remains infamous for its brutal lawnmower scene.

men read from the book and unleash an unspeakable evil upon themselves. The film that started Bruce Campbell’s career as a butch horror movie ass-kicker, The Evil Dead remains a stylish, creepy, and hilarious take on the zombie genre. Raimi followed it up with two equally classic sequels: The Evil Dead 2 (1987) and Army of Darkness (1992). The films get increasingly silly and slapsticky as they go along and hence—in my humble opinion—lose the subtle, black humor of the original. The 1980s and early 90s also the release of other classic zombie comedies such as The Return of the Living Dead (1985), which spawned its own massive series of films, and Peter Jackson’s Dead Alive (1992), which remains infamous for its brutal lawnmower scene.

The trailer for Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead.

The infamous lawnmower scene from Peter Jackson’s Dead Alive—this an extremely gory scene and requires you to log into Youtube to see it.

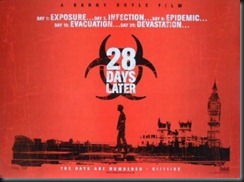

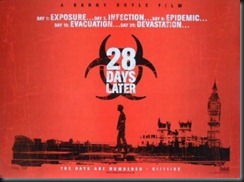

Zombie films have proliferated so widely in he last ten years that it is impossible to comment upon all of them. From the dystopian future of zombie slaves in Fido (2006) to zombie comedies like Shaun of the Dead, Zombieland (2009), and Zombie Strippers (2008), the past decade of cinema has seen zombie films appear at an unprecedented rate, particularly if one considers the direct-to-video market. But amongst the proliferation of zombie texts, one film deserves special mention—Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later (2002), a powerfully visceral and existential film that explores the primal core of humanity. Boyle’s film proves so revolutionary because its zombies do not walk slowly like they are in the grips of rigor mortis but instead sprint at their victims like psychotic PCP fiends. While some might argue that Boyle’s film is not technically about zombie because they are not undead but instead infected by a rage virus, the film still features hordes of mindless humans who have been robbed of reason in manner akin to zombie cinema. Boyle uses these fast-moving zombies to brutal effect and explores the primal rage that lies at the heart of the human condition. Boyle blurs the line between the infected and the normal humans to the point where we can no longer tell if the zombies are actually any different than normal humans.

and existential film that explores the primal core of humanity. Boyle’s film proves so revolutionary because its zombies do not walk slowly like they are in the grips of rigor mortis but instead sprint at their victims like psychotic PCP fiends. While some might argue that Boyle’s film is not technically about zombie because they are not undead but instead infected by a rage virus, the film still features hordes of mindless humans who have been robbed of reason in manner akin to zombie cinema. Boyle uses these fast-moving zombies to brutal effect and explores the primal rage that lies at the heart of the human condition. Boyle blurs the line between the infected and the normal humans to the point where we can no longer tell if the zombies are actually any different than normal humans.

Hence, Zombie cinema is alive and well and seems to have no sign of slowing down: Resident Evil films continue to appear, Romero releases new entries in his series, zombie horror films and comedies appear in the U.S. market and abroad in countries like France, and the zombie becomes a source of satire on sitcoms like Community. The zombie has become a cultural icon and myth because it epitomizes the way that most of us feel at one time or another—we are the oppressed and the docile who fall in line, take orders endlessly, and consume mindless garbage day after day after day after day……

eternal life, but they were eventually executed and crows plucked out their eyes. A creepy and stylish supernatural film, Tombs of the Blind Dead is not exactly a zombie film in the Romero sense—the Templars are not rotten-looking corpses but instead bear a stronger

eternal life, but they were eventually executed and crows plucked out their eyes. A creepy and stylish supernatural film, Tombs of the Blind Dead is not exactly a zombie film in the Romero sense—the Templars are not rotten-looking corpses but instead bear a stronger  resemblance to mummies. Additionally, they are not mindless like Romero’s zombies but instead retain their deadly purpose even in their reanimated forms. However, they do return from the grave to feast on the flesh of the living, so the film is still pure zombie at its core. The film became a cult hit and lead to three sequels that further developed the tale of the undead Templars: Return of the Blind Dead (1973), The Ghost Galleon (1974), and Night of the Seagulls (1975). All four films have gone on to become highly influential horror classics whether one considers them to be zombie films or not—Ossorio himself holds that they are not zombie films. The

resemblance to mummies. Additionally, they are not mindless like Romero’s zombies but instead retain their deadly purpose even in their reanimated forms. However, they do return from the grave to feast on the flesh of the living, so the film is still pure zombie at its core. The film became a cult hit and lead to three sequels that further developed the tale of the undead Templars: Return of the Blind Dead (1973), The Ghost Galleon (1974), and Night of the Seagulls (1975). All four films have gone on to become highly influential horror classics whether one considers them to be zombie films or not—Ossorio himself holds that they are not zombie films. The early 1970s also saw the release of Spanish director Jorge Grau’s stylish, beautifully filmed and twisted zombie classic: Let Sleeping Corpses Lie (a.k.a. The Living Dead at the Manchester Morgue; 1974). Shot on location in the English countryside, Let Sleeping Corpses Lie followed in the Romero zombie tradition. The film concerns an experimental machine that uses ultra-sonic waves to cause bugs to kill one another off, thus protecting crops from damage. But, of course, the machine begins to cause the dead to return from the grave.

early 1970s also saw the release of Spanish director Jorge Grau’s stylish, beautifully filmed and twisted zombie classic: Let Sleeping Corpses Lie (a.k.a. The Living Dead at the Manchester Morgue; 1974). Shot on location in the English countryside, Let Sleeping Corpses Lie followed in the Romero zombie tradition. The film concerns an experimental machine that uses ultra-sonic waves to cause bugs to kill one another off, thus protecting crops from damage. But, of course, the machine begins to cause the dead to return from the grave.

Peeping Tom is brilliant, and it still floors me that it ruined Michael Powell's career when Hitchcock only gained popularity after Psycho.

ReplyDeleteI love the very early Powell films I've seen that he did with Pressburger--particularly I Know Where I'm Going!, 49th Parallel, and The Edge of the World. Part of the problem with Peeping Tom, I guess, is that it was nothing like any of these films except that they shared a certain element of grittiness that I find hard to pin down. It's not Cassavetes-gritty, but it's a type of grittiness that is often buffed out of early Hollywood films.

I've always equated Peeping Tom with Hitchcock's Frenzy. Peeping Tom may even be creepier because it lacks the levity that Hitchcock can't help but interject (like Frenzy's scene with the corpse in the back of the potato truck). The only thing wrong with Peeping Tom, I think, was that it was made a dozen years before its time.