Across the 20th century, alien invasion narratives became a staple of both science fiction literature and film. In 1898, H.G. Wells published The War of the Worlds, which was the first story to feature a conflict between Earth and an alien species. The War of the Worlds concerns the invasion of Earth by hostile Martians. They terrorize the planet and kill indiscriminately in their walkers, machines that already prefigure the AT-AT walkers of The Empire Strikes Back (1980). Ultimately, the Martians are defeated by their inability to adapt to common Earthborn diseases. While some alien stories occurred in the intervening years, the genre truly took off after the onset of the Cold War. Of course, there is another classic instance before the 1950s: American director Orson Welles’ (Citizen Kane [1941], The Lady from Shanghai [1947], Touch of Evil [1958], etc.) 1938 radio show adaptation of War of the Worlds.  Welles’ radio broadcast presented the story of the novel as if it was a series of live news casts. Unaccustomed to such presentations, the American public fell into a panic believing that the Earth was actually being invaded. The effects of Welles’ broadcast indicate the power that the concept of aliens continues to wield in modern culture, particularly in the United States. Not only did alien invasion become an archetypal sci-fi plot, but it also began to seep into the popular unconscious, giving rise to conspiracy theories and alien abduction stories in the latter half of the century. Hence, since Welles’ broadcast, alien invasion stories have maintained a link to cultural paranoia and fear into which authors and directors have often tapped in order to explore not just themes of the Other but also socio-political issues.

Welles’ radio broadcast presented the story of the novel as if it was a series of live news casts. Unaccustomed to such presentations, the American public fell into a panic believing that the Earth was actually being invaded. The effects of Welles’ broadcast indicate the power that the concept of aliens continues to wield in modern culture, particularly in the United States. Not only did alien invasion become an archetypal sci-fi plot, but it also began to seep into the popular unconscious, giving rise to conspiracy theories and alien abduction stories in the latter half of the century. Hence, since Welles’ broadcast, alien invasion stories have maintained a link to cultural paranoia and fear into which authors and directors have often tapped in order to explore not just themes of the Other but also socio-political issues.

The alien invasion genre remains mostly predominant in American science fiction, and this can be traced back to a variety of historical events. In 1944, the Germans begin launching V-2 rockets on Britain. The V-2 rocket is the first rocket to reach a height of 100 km. On July 16, 1945, the United States government tests the first atomic bomb in New Mexico. August 6th and 9th, 1945, the United States drops the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing more than 150,000 people. While 1945 signaled the the end of World War II, it simultaneously heralded the beginning of the Cold War—the United States and the U.S.S.R. settled into a state of paranoid watchfulness. In 1947, an unidentified aircraft crashes in Roswell, New Mexico. Stories appear claiming that a UFO was recovered, but this are later retracted, and the United States government claims that it was nothing more than a weather balloon. Many believers in UFOs (ufologists) maintain that an alien space craft crash-landed and that the United States recovered Alien corpses but subsequently covered up the findings. In 1950, Joseph McCarthy begins arguing that large numbers of

The alien invasion genre remains mostly predominant in American science fiction, and this can be traced back to a variety of historical events. In 1944, the Germans begin launching V-2 rockets on Britain. The V-2 rocket is the first rocket to reach a height of 100 km. On July 16, 1945, the United States government tests the first atomic bomb in New Mexico. August 6th and 9th, 1945, the United States drops the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing more than 150,000 people. While 1945 signaled the the end of World War II, it simultaneously heralded the beginning of the Cold War—the United States and the U.S.S.R. settled into a state of paranoid watchfulness. In 1947, an unidentified aircraft crashes in Roswell, New Mexico. Stories appear claiming that a UFO was recovered, but this are later retracted, and the United States government claims that it was nothing more than a weather balloon. Many believers in UFOs (ufologists) maintain that an alien space craft crash-landed and that the United States recovered Alien corpses but subsequently covered up the findings. In 1950, Joseph McCarthy begins arguing that large numbers of communist subversives have infiltrated the United States. November 1, 1952—the United States tests the first hydrogen bomb on the Marshall Islands. In 1953, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg are executed as traitors for passing information about the atomic bomb to the Soviet Union. On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launches the satellite Sputnik, which reaches a height of 250 km. In 1960, a United States U-2 reconnaissance plane is shot down over the Soviet Union. The U.S. and the U.S.S.R. continue to escalate in the nuclear arms race and the space race across the 1960s. Against this backdrop of mass death, conspiracy, espionage, paranoia and space travel, science fiction developed into a fully mature genre in the 1950s and 60s, and the sub-genre of alien invasion texts became a common means of depicting and criticizing the socio-political atmosphere of the time.

communist subversives have infiltrated the United States. November 1, 1952—the United States tests the first hydrogen bomb on the Marshall Islands. In 1953, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg are executed as traitors for passing information about the atomic bomb to the Soviet Union. On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launches the satellite Sputnik, which reaches a height of 250 km. In 1960, a United States U-2 reconnaissance plane is shot down over the Soviet Union. The U.S. and the U.S.S.R. continue to escalate in the nuclear arms race and the space race across the 1960s. Against this backdrop of mass death, conspiracy, espionage, paranoia and space travel, science fiction developed into a fully mature genre in the 1950s and 60s, and the sub-genre of alien invasion texts became a common means of depicting and criticizing the socio-political atmosphere of the time.

The 1950s and 60s saw the publication of numerous science fiction novels that dealt with aliens and/or extraterrestrial invasion. Arthur C. Clarke, one of science fiction’s more influential authors, published Childhood End (1953), which depicts a peaceful invasion of Earth by an alien species known as the Overlords, who have an appearance similar to classic depictions of Satan. The Overlords’ invasion ends all war on earth, creates a worldwide government, and transforms the Earth into a global utopia. Soon, the children of Earth begin to manifest psychic abilities as they evolve towards a gestalt, group consciousness, and the adults are left behind in the wake. Another sci-fi master, Robert Heinlein, published numerous works dealing with alien species, particularly Starship Troopers (1959) and Stranger in a Strange Land (1961). The subject of extreme

The 1950s and 60s saw the publication of numerous science fiction novels that dealt with aliens and/or extraterrestrial invasion. Arthur C. Clarke, one of science fiction’s more influential authors, published Childhood End (1953), which depicts a peaceful invasion of Earth by an alien species known as the Overlords, who have an appearance similar to classic depictions of Satan. The Overlords’ invasion ends all war on earth, creates a worldwide government, and transforms the Earth into a global utopia. Soon, the children of Earth begin to manifest psychic abilities as they evolve towards a gestalt, group consciousness, and the adults are left behind in the wake. Another sci-fi master, Robert Heinlein, published numerous works dealing with alien species, particularly Starship Troopers (1959) and Stranger in a Strange Land (1961). The subject of extreme  controversy, Starship Troopers concerned a future version of Earth in which only individuals who served in the military were qualified to be citizens and vote. These soldiers are trained in a fashion similar to the marines and then are dropped from space onto an alien planet where they fight the local population of bug-like aliens. In this story, we (human beings) are the alien

controversy, Starship Troopers concerned a future version of Earth in which only individuals who served in the military were qualified to be citizens and vote. These soldiers are trained in a fashion similar to the marines and then are dropped from space onto an alien planet where they fight the local population of bug-like aliens. In this story, we (human beings) are the alien  invaders. Heinlein’s novel proved controversial because of its depiction of fascism and militarism—it remains ambiguous about its judgment of this society and its preemptive strike attitude. The novel was later adapted by Dutch filmmaker Paul Verhoeven (Robocop [1987], Total Recall [1990], Basic Instinct [1992], Showgirls [1995]) into the 1997 film of the same name. Verhoeven’s film has gone on to develop its own cult classic status as either a brilliant piece of sci-fi satire or one of the worst, most cheesy science fiction films ever made. Indeed, Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers often feels like he is making trying to make an episode of Beverly Hill, 90210 or Saved by the Bell in which the cast all decide to become space marines. Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, on the other hand, is often considered to be one of the great masterpieces of the science fiction genre. It tells the story of a human, Valentine Michael Smith, who was left behind

invaders. Heinlein’s novel proved controversial because of its depiction of fascism and militarism—it remains ambiguous about its judgment of this society and its preemptive strike attitude. The novel was later adapted by Dutch filmmaker Paul Verhoeven (Robocop [1987], Total Recall [1990], Basic Instinct [1992], Showgirls [1995]) into the 1997 film of the same name. Verhoeven’s film has gone on to develop its own cult classic status as either a brilliant piece of sci-fi satire or one of the worst, most cheesy science fiction films ever made. Indeed, Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers often feels like he is making trying to make an episode of Beverly Hill, 90210 or Saved by the Bell in which the cast all decide to become space marines. Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, on the other hand, is often considered to be one of the great masterpieces of the science fiction genre. It tells the story of a human, Valentine Michael Smith, who was left behind  on Mars as a child and raised by Martians. The book chronicles his return to Earth and his rise to messianic status. He exhibits psychic abilities and a superhuman level of intelligence, but he seems like a child in many of his relations with Earth culture. The novel introduces the concept of grokking—”to grok” is to understand something on such a fundamental level that the observed and the observer become intermixed with one another. Heinlein’s publisher cut the novel’s length down by almost 60,000 words, eliminating many of the novel’s graphic sex scenes, religious criticism, and socio-political critique. Mind-bendingly surreal, Stranger in a Strange Land remains paradigmatic of the soon to come hippie movement and its ideals of free love and anti-traditional politics, but it simultaneously transcends its time period to explore fundamental metaphysical and psychological questions of identity and knowledge. The novel also demonstrates how aliens can be used to interrogate the human and how alien species always inevitably interrogate our relation to the Other.

on Mars as a child and raised by Martians. The book chronicles his return to Earth and his rise to messianic status. He exhibits psychic abilities and a superhuman level of intelligence, but he seems like a child in many of his relations with Earth culture. The novel introduces the concept of grokking—”to grok” is to understand something on such a fundamental level that the observed and the observer become intermixed with one another. Heinlein’s publisher cut the novel’s length down by almost 60,000 words, eliminating many of the novel’s graphic sex scenes, religious criticism, and socio-political critique. Mind-bendingly surreal, Stranger in a Strange Land remains paradigmatic of the soon to come hippie movement and its ideals of free love and anti-traditional politics, but it simultaneously transcends its time period to explore fundamental metaphysical and psychological questions of identity and knowledge. The novel also demonstrates how aliens can be used to interrogate the human and how alien species always inevitably interrogate our relation to the Other.

While the novels of Clarke and Heinlein prove intensely cerebral, the 1950s and 60s also saw the rise of the science fiction film as a significant force in the Hollywood marketplace but in a distinctly watered-down style. Studios churned out B-level sci-fi horror cinema by the boatload, a large portion of which dealt with lingering fears from World War II and the Cold War. We will be watching one of the great classics from this period in class: Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956). Body Snatchers is a film about the paranoia that developed in the United States during the 1950s. Don Siegel’s original cinematic adaptation of Jack Finney’s novel The Body Snatchers (1955) has been remade three additional times in 1978, 1993, and 2007. While the original Body Snatchers was part of 1950s

While the novels of Clarke and Heinlein prove intensely cerebral, the 1950s and 60s also saw the rise of the science fiction film as a significant force in the Hollywood marketplace but in a distinctly watered-down style. Studios churned out B-level sci-fi horror cinema by the boatload, a large portion of which dealt with lingering fears from World War II and the Cold War. We will be watching one of the great classics from this period in class: Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956). Body Snatchers is a film about the paranoia that developed in the United States during the 1950s. Don Siegel’s original cinematic adaptation of Jack Finney’s novel The Body Snatchers (1955) has been remade three additional times in 1978, 1993, and 2007. While the original Body Snatchers was part of 1950s sci-fi cinema, Philip Kaufman’s 1978 version remains equally famous for its body horror take on the story. The unremarkable 1993 version was directed by transgressive/independent cinema icon Abel Ferrara (The Driller Killer [1979], King of New York [1990], Bad Lieutenant [1992], and New Rose Hotel [1998]). Also unremarkable, the 2007 adaptation entitled The Invasion starring Nicole Kidman and Daniel Craig failed to develop the story in any original or meaningful way.

sci-fi cinema, Philip Kaufman’s 1978 version remains equally famous for its body horror take on the story. The unremarkable 1993 version was directed by transgressive/independent cinema icon Abel Ferrara (The Driller Killer [1979], King of New York [1990], Bad Lieutenant [1992], and New Rose Hotel [1998]). Also unremarkable, the 2007 adaptation entitled The Invasion starring Nicole Kidman and Daniel Craig failed to develop the story in any original or meaningful way.

Aside from Body Snatchers, several other American 1950s and 60s sci-fi thrillers bear mentioning: The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), The Thing from Another World (1951), Invaders from Mars (1953), Them! (1954), and Forbidden Planet (1956). In Robert Wise’s (West Side Story [1961], The Haunting [1963], The Sound of Music [1965], The Andromeda Strain [1971], and Star Trek: The Motion Picture [1979])  The Day the Earth Stood Still [1951], an alien space craft lands in Washington, D.C. The flying saucer contains a humanoid but extraterrestrial emissary named Klaatu and his robot Gort who have come with a warning for the people of Earth. When Klaatu cannot deliver his message to the entire world because of the divisions between nations, he escapes from his captors in D.C., poses as a human, and lives with a typical suburban family. Ultimately, The Day the Erath Stood Still remains a classic anti-war statement about the need for international cooperation and respect. If humankind cannot get their act together, then dire consequences may result. The same year as The Day the Earth Stood Still also saw the release of Howard Hawk’s production entitled The Thing from Another World, which

The Day the Earth Stood Still [1951], an alien space craft lands in Washington, D.C. The flying saucer contains a humanoid but extraterrestrial emissary named Klaatu and his robot Gort who have come with a warning for the people of Earth. When Klaatu cannot deliver his message to the entire world because of the divisions between nations, he escapes from his captors in D.C., poses as a human, and lives with a typical suburban family. Ultimately, The Day the Erath Stood Still remains a classic anti-war statement about the need for international cooperation and respect. If humankind cannot get their act together, then dire consequences may result. The same year as The Day the Earth Stood Still also saw the release of Howard Hawk’s production entitled The Thing from Another World, which featured a group of Antarctic scientists unearthing a spaceship that had been buried beneath the ice in prehistoric times, a plotline that recalls H.P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness (1931). They uncover a frozen body, take it back to base, and inadvertently thaw it out. The creature which emerges ends up being a super-advanced form of plant life that feeds on blood. The Thing, as the film is often abbreviated, concerns the possibility (again a Lovecraftian one) that our Earth harbors secrets that would prove harmful if discovered. A parable about scientific curiosity, The Thing also imagines how advanced forms of life could evolve from non-animal source—it was remade into a classic body horror film by horror icon John Carpenter in 1982. See the next blog entry for more on Carpenter’s remake.

featured a group of Antarctic scientists unearthing a spaceship that had been buried beneath the ice in prehistoric times, a plotline that recalls H.P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness (1931). They uncover a frozen body, take it back to base, and inadvertently thaw it out. The creature which emerges ends up being a super-advanced form of plant life that feeds on blood. The Thing, as the film is often abbreviated, concerns the possibility (again a Lovecraftian one) that our Earth harbors secrets that would prove harmful if discovered. A parable about scientific curiosity, The Thing also imagines how advanced forms of life could evolve from non-animal source—it was remade into a classic body horror film by horror icon John Carpenter in 1982. See the next blog entry for more on Carpenter’s remake.

Similar to Body Snatchers, Invaders from Mars follows a young boy who witnesses a flying saucer landing near his house one night and then notices how is father has started acting in a loveless and even hostile manner. Increasingly, the townspeople begin to all act in a similarly bizarre manner, and the young boy notices that  strange marks appear on the necks of the afflicted. No one believes him until a local astronomer helps him determine that the people are being reprogrammed by a Martian spaceship. The film features similar themes to Invasion of the Body Snatchers, such as secret infiltration, brainwashing, and secret agents of an foreign power.

strange marks appear on the necks of the afflicted. No one believes him until a local astronomer helps him determine that the people are being reprogrammed by a Martian spaceship. The film features similar themes to Invasion of the Body Snatchers, such as secret infiltration, brainwashing, and secret agents of an foreign power.

The 1950s and 60s also saw the rise of a different—but often related—sub-genre of science fiction: the giant monster film. In American cinema, the giant monsters were usually the product of radiation, chemicals, gamma rays, etc. Without a doubt the most classic example of this sub genre is Them!, which depicts the discovery of gigantic ants created from atomic experiments in New Mexico.  Them! paved the way for a variety of films concerning giant mantises, tarantulas, etc. These giant monster films would mostly die out after the 60s and instead give way to killer animal films like Jaws, Piranha, Grizzly, etc. Both genres still remain vibrant on the Sci-Fi Network where they are churned out en-masse for those who enjoy purposefully cheesy and hilarious sci-fi/horror cinema. One final film that bears mentioning from this period is Forbidden Planet, a science fiction re-telling of William Shakespeare’s The Tempest. In Forbidden Planet, a group of astronauts journeys to a distant planet to investigate the fate of an expedition that had gone missing twenty years earlier. They only find three survivors: the brilliant Dr. Morbius, his daughter Altaira, and Robby the advanced robot invented by the Morbius. Robby the Robot went on to become an iconic sci-fi figure because he was one of the earliest robots in cinema to feature a personality and a complicated appearance. Morbius’s crew and wife died mysteriously years earlier and Morbius devoted his subsequent life to studying the seemingly extinct alien species, the Krell,

Them! paved the way for a variety of films concerning giant mantises, tarantulas, etc. These giant monster films would mostly die out after the 60s and instead give way to killer animal films like Jaws, Piranha, Grizzly, etc. Both genres still remain vibrant on the Sci-Fi Network where they are churned out en-masse for those who enjoy purposefully cheesy and hilarious sci-fi/horror cinema. One final film that bears mentioning from this period is Forbidden Planet, a science fiction re-telling of William Shakespeare’s The Tempest. In Forbidden Planet, a group of astronauts journeys to a distant planet to investigate the fate of an expedition that had gone missing twenty years earlier. They only find three survivors: the brilliant Dr. Morbius, his daughter Altaira, and Robby the advanced robot invented by the Morbius. Robby the Robot went on to become an iconic sci-fi figure because he was one of the earliest robots in cinema to feature a personality and a complicated appearance. Morbius’s crew and wife died mysteriously years earlier and Morbius devoted his subsequent life to studying the seemingly extinct alien species, the Krell,  who used to inhabit the planet. Altaira, like Miranda in The Tempest, has never had contact with other human aside from her father, and she quickly falls in love with the lead astronaut. Soon, a bizarre invisible force begins wreaking havoc on the astronauts. Does it represent a survivor of the Krell? Did the advanced society of the Krell create technology so advanced that they destroyed themselves? I won’t ruin the film, but it remains a compelling and entertaining exploration of the limits of science, the possibilities of advanced alien civilizations, and how the lack of society can affect identity. The B-movie sci-fi of the 50s and 60s can seem rather naïve and primitive now, but it is still compelling and often hilarious cinema for those willing to accept its more simplistic visuals, values, and narratives.

who used to inhabit the planet. Altaira, like Miranda in The Tempest, has never had contact with other human aside from her father, and she quickly falls in love with the lead astronaut. Soon, a bizarre invisible force begins wreaking havoc on the astronauts. Does it represent a survivor of the Krell? Did the advanced society of the Krell create technology so advanced that they destroyed themselves? I won’t ruin the film, but it remains a compelling and entertaining exploration of the limits of science, the possibilities of advanced alien civilizations, and how the lack of society can affect identity. The B-movie sci-fi of the 50s and 60s can seem rather naïve and primitive now, but it is still compelling and often hilarious cinema for those willing to accept its more simplistic visuals, values, and narratives.

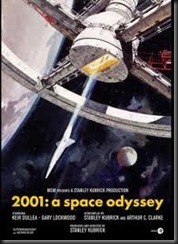

While B-movie sci-fi dominated the 1950s and 60s, the 1960s did see the release of one of the greatest science fiction films of all time—it also remains one of the great works of cinema more generally. A pivotal year of political revolution, 1968 saw the release of Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Inspired by an earlier story of Clarke’s entitled “The Sentinel,” which concerned an alien artifact being unearthed on the moon, Clarke and Stanley Kubrick co-wrote the novel and the screenplay of 2001 simultaneously. Kubrick’s (Dr. Strangelove [1964], A Clockwork Orange [1971], The Shining [1980], Full Metal Jacket [1987], and Eyes Wide Shut [1999]), 2001: A Space Odyssey remains much more ambiguous than Clarke’s novel—Clarke wrote numerous sci-fi classics including Childhood’s End (mentioned above), Rendezvous with Rama [1972], and the three sequels to 2001: 2010: Odyssey Two [1982], 2061: Odyssey Three [1987], and 3001: The Final Odyssey [1997]. Both the novel and the film concern evolution, the potential for the rise of new forms of intelligent life, and the possibility of humanity evolving beyond its current state. 2001 depicts evolution being driven by beings of a higher intelligence—Clarke’s series of novels makes it apparent that the beings are aliens, but Kubrick’s film leaves open the possibility that humankind enters into communication with the divine. 2001 depicts three distinct moments of evolution. The film opens with a group of apelike creatures scraping out a meager existence on weeds,bugs, and other small snacks. Suddenly, a giant black rectangle (known as the monolith) appears among them. After their interaction with the monolith, the ape creatures develop the ability to use tools and hunt animals. The film then jumps ahead several thousand years via a match cut to the discovery of a similar

ambiguous than Clarke’s novel—Clarke wrote numerous sci-fi classics including Childhood’s End (mentioned above), Rendezvous with Rama [1972], and the three sequels to 2001: 2010: Odyssey Two [1982], 2061: Odyssey Three [1987], and 3001: The Final Odyssey [1997]. Both the novel and the film concern evolution, the potential for the rise of new forms of intelligent life, and the possibility of humanity evolving beyond its current state. 2001 depicts evolution being driven by beings of a higher intelligence—Clarke’s series of novels makes it apparent that the beings are aliens, but Kubrick’s film leaves open the possibility that humankind enters into communication with the divine. 2001 depicts three distinct moments of evolution. The film opens with a group of apelike creatures scraping out a meager existence on weeds,bugs, and other small snacks. Suddenly, a giant black rectangle (known as the monolith) appears among them. After their interaction with the monolith, the ape creatures develop the ability to use tools and hunt animals. The film then jumps ahead several thousand years via a match cut to the discovery of a similar  black

black  artifact under the surface of the Moon. This second monolith ends up emitting a signal that points into the depths of the Solar System—Jupiter in the film, Saturn in the novel. The novel then flashes forward to a segment concerning the Discovery’s mission to investigate the signal’s target around Jupiter. The ship is piloted by an advanced computer known as HAL-9000, or simply Hal. Hal runs all of the ship’s basic systems and has visual and audio capacities that allow him to interact with the astronauts like any other crew member. He has no bodily manifestation, but his presence remains felt throughout the ship thanks to the red-eyed cameras that allow him to see everything—Kubrick often cuts to fish-eyed lens shots to give us the

artifact under the surface of the Moon. This second monolith ends up emitting a signal that points into the depths of the Solar System—Jupiter in the film, Saturn in the novel. The novel then flashes forward to a segment concerning the Discovery’s mission to investigate the signal’s target around Jupiter. The ship is piloted by an advanced computer known as HAL-9000, or simply Hal. Hal runs all of the ship’s basic systems and has visual and audio capacities that allow him to interact with the astronauts like any other crew member. He has no bodily manifestation, but his presence remains felt throughout the ship thanks to the red-eyed cameras that allow him to see everything—Kubrick often cuts to fish-eyed lens shots to give us the  impression of seeing from Hal’s perspective. Only two crew members are actually awake—Dave Bowman and Frank Poole. The rest of the crewmembers sleep in hibernation chambers until they are needed around Jupiter. Hal eventually malfunctions, kills the sleeping crewmembers and Frank, and attempts to kill Dave. Dave manages to shutdown Hal and continue the mission. He discovers a gigantic monolith hovering in orbit around Jupiter and enters it using one of the ship’s explorer pods. He passes into a dimension beyond time and space and what occurs beyond this point in the film has remained the subject of endless speculation with critics. Dave witnesses various alien

impression of seeing from Hal’s perspective. Only two crew members are actually awake—Dave Bowman and Frank Poole. The rest of the crewmembers sleep in hibernation chambers until they are needed around Jupiter. Hal eventually malfunctions, kills the sleeping crewmembers and Frank, and attempts to kill Dave. Dave manages to shutdown Hal and continue the mission. He discovers a gigantic monolith hovering in orbit around Jupiter and enters it using one of the ship’s explorer pods. He passes into a dimension beyond time and space and what occurs beyond this point in the film has remained the subject of endless speculation with critics. Dave witnesses various alien star systems in one of the great psychedelic sequences in filmic history. In Clarke’s 2010: Odyssey Two, we learn that Dave’s final transmission was “My God. It’s full of stars.” After the long journey through various galaxies, he then arrives in a bizarre white room where he witnesses himself at various stages of life including extreme old age. As his old body lays in bed on the verge of death, another monolith appears in front of him. The film then cuts to its final image, an image of Earth from space and the glowing sphere of a fetus hovering in orbit above the planet. In Clarke’s novel and its sequels, the monoliths are created by aliens who have sought out species with the potential to evolve intelligence and aided them along their evolutionary path. Kubrick’s film is more subtle: we are never sure whether

star systems in one of the great psychedelic sequences in filmic history. In Clarke’s 2010: Odyssey Two, we learn that Dave’s final transmission was “My God. It’s full of stars.” After the long journey through various galaxies, he then arrives in a bizarre white room where he witnesses himself at various stages of life including extreme old age. As his old body lays in bed on the verge of death, another monolith appears in front of him. The film then cuts to its final image, an image of Earth from space and the glowing sphere of a fetus hovering in orbit above the planet. In Clarke’s novel and its sequels, the monoliths are created by aliens who have sought out species with the potential to evolve intelligence and aided them along their evolutionary path. Kubrick’s film is more subtle: we are never sure whether  Dave encounters aliens or is somehow granted access into the divine force that drives the universe. Ultimately, the film questions whether advanced aliens would be any different than gods to us. While they differ in levels of ambiguity, both Kubrick and Clarke’s texts trace the evolutionary force from the pre-neolithic era to the potential for posthuman development. They imagine how the human could progress beyond its current bodily and intellectual limitations. 2001 remains not only just one of the greatest science fiction films ever made but also one of the purest experiences of cinema as cinema. From its opening moments, it bathes the viewer in images and

Dave encounters aliens or is somehow granted access into the divine force that drives the universe. Ultimately, the film questions whether advanced aliens would be any different than gods to us. While they differ in levels of ambiguity, both Kubrick and Clarke’s texts trace the evolutionary force from the pre-neolithic era to the potential for posthuman development. They imagine how the human could progress beyond its current bodily and intellectual limitations. 2001 remains not only just one of the greatest science fiction films ever made but also one of the purest experiences of cinema as cinema. From its opening moments, it bathes the viewer in images and  sound without ever explaining itself. Structured like a symphony and tied together by the Dawn section of Richard Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra (1896), a tone poem inspired by Friedrich Nietzsche’s Thus Sprach Zarathustra (1883-5). Nietzsche’s Zarathustra was his attempt to sketch the future of humanity, the ubermensch; therefore, Zarathustra provides one of the underlying themes of the film—it is about the nature of becoming something more than what we are at present. 2001 represented the cerebral side of 50s and 60s sci-fi, but the bulk of films remained in the b-movie tradition.

sound without ever explaining itself. Structured like a symphony and tied together by the Dawn section of Richard Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra (1896), a tone poem inspired by Friedrich Nietzsche’s Thus Sprach Zarathustra (1883-5). Nietzsche’s Zarathustra was his attempt to sketch the future of humanity, the ubermensch; therefore, Zarathustra provides one of the underlying themes of the film—it is about the nature of becoming something more than what we are at present. 2001 represented the cerebral side of 50s and 60s sci-fi, but the bulk of films remained in the b-movie tradition.

While American theaters saw an unending onslaught of b-level sci-fi/horror being released in the 1950s and 60s, Japanese cinema also saw the rise of a similar wave of films that often dealt with many of the same socio-political and scientific fears of its American counterparts. In particular, 1954 saw the release of Ishiro Honda’s classic Gojira (or Godzilla), the first in a long line of kaiju, giant monster films. Gojira concerns a giant lizard creature who arises from the ocean and begins attacking Japan after a series of atomic bomb tests. Of course, he attacks the cities and kill thousands of citizens. In essence, the monster Godzilla signifies the

While American theaters saw an unending onslaught of b-level sci-fi/horror being released in the 1950s and 60s, Japanese cinema also saw the rise of a similar wave of films that often dealt with many of the same socio-political and scientific fears of its American counterparts. In particular, 1954 saw the release of Ishiro Honda’s classic Gojira (or Godzilla), the first in a long line of kaiju, giant monster films. Gojira concerns a giant lizard creature who arises from the ocean and begins attacking Japan after a series of atomic bomb tests. Of course, he attacks the cities and kill thousands of citizens. In essence, the monster Godzilla signifies the  atomic bomb and its power to destroy entire cities, but it also represents the environmental hazards posed by the bomb. In the wake of Gojira’s popularity, a slew of sequels and spin-offs were released that built an entire universe of prehistoric creatures, mutants, and aliens that battle each other, attempt to destroy humankind, or fight to preserve humanity against other invading monsters. Once the destroyer of humankind, Godzilla later becomes Japan’s protector. In the coming years, audiences were introduced to a wide array of creatures including Mothra (the gigantic moth guardian of a tiny island),

atomic bomb and its power to destroy entire cities, but it also represents the environmental hazards posed by the bomb. In the wake of Gojira’s popularity, a slew of sequels and spin-offs were released that built an entire universe of prehistoric creatures, mutants, and aliens that battle each other, attempt to destroy humankind, or fight to preserve humanity against other invading monsters. Once the destroyer of humankind, Godzilla later becomes Japan’s protector. In the coming years, audiences were introduced to a wide array of creatures including Mothra (the gigantic moth guardian of a tiny island),  Gamera (a giant flying turtle creature), Rodan (a mutated flying dinosaur—the name is a contraction of pteranodan), Ghidorah (a three-headed dragon), and Mechagodzilla (Godzilla’s mechanical doppleganger). All of these monsters would appear in numerous sequels and crossovers from the 1950s to the present. Godzilla even began to crossover with the great giant monster of Golden Age American cinema: King Kong (1933). Some of the kaiju monsters did actually come from space like Ghidorah, but 1950s-60s Japaense sci-fi cinema also featured more conventional alien tales like Ishiro Honda’s Battle in Outer Space or Atragon, which features aliens not from outer space but from the depths of the ocean where the lost continent of Mu continues to thrive. The Japanese sci-fi cinema in the 1950s and 60s feels almost exactly like its American counterpart, probably because both are dealing with similar socio-political anxieties.

Gamera (a giant flying turtle creature), Rodan (a mutated flying dinosaur—the name is a contraction of pteranodan), Ghidorah (a three-headed dragon), and Mechagodzilla (Godzilla’s mechanical doppleganger). All of these monsters would appear in numerous sequels and crossovers from the 1950s to the present. Godzilla even began to crossover with the great giant monster of Golden Age American cinema: King Kong (1933). Some of the kaiju monsters did actually come from space like Ghidorah, but 1950s-60s Japaense sci-fi cinema also featured more conventional alien tales like Ishiro Honda’s Battle in Outer Space or Atragon, which features aliens not from outer space but from the depths of the ocean where the lost continent of Mu continues to thrive. The Japanese sci-fi cinema in the 1950s and 60s feels almost exactly like its American counterpart, probably because both are dealing with similar socio-political anxieties.

This brief history demonstrates how the alien invasion story archetype became a paradigmatic way of examining current socio-political anxieties, but we will see how alien films begin to push into more psychological space as well next week…

No comments:

Post a Comment